The coronavirus crisis affects us all, regardless of the industry. The market research industry is no exception. The conduct of qualitative market research, in particular, has been impacted, since qualitative interviews or focus groups can now only be conducted remotely. A prospect asked me last week about the methodological adjustments resulting from the Coronavirus crisis. Virtualisation is, of course, the first answer and it is recommended by ESOMAR. But are remote qualitative interviews still as effective? How is communication affected by distance? A publication by my friend Dr Emmanuel Tourpe gave me the excuse to answer this question.

Remote qualitative research

Containment raises the question of the continuity of activities and in particular qualitative studies. Ethnography, participatory observation and Design Thinking projects are no longer possible under the current conditions. Unless, of course, you are interested in what consumers are doing in their homes, in which case the timing is ideal.

But what about focus groups and other face-to-face interviews? ESOMAR’s guidelines are clear: on-line methodologies should be used whenever possible. We already carry out a lot of remote interviews via Skype, WebEx or other equivalent means. But for focus groups, it’s a different story.

Concretely and precisely, I doubt that a semi-structured or “free” qualitative interview can be conducted with the same result on-line. The lack of physical proximity is inevitably felt on the interviewer’s ability to put his interlocutor at ease, to have his complete attention, and to deepen the subjects with the same efficiency. On the other hand, I think that guided interviews can be conducted on-line without any noticeable loss of quality.

The impact of distance on the quality of the communication

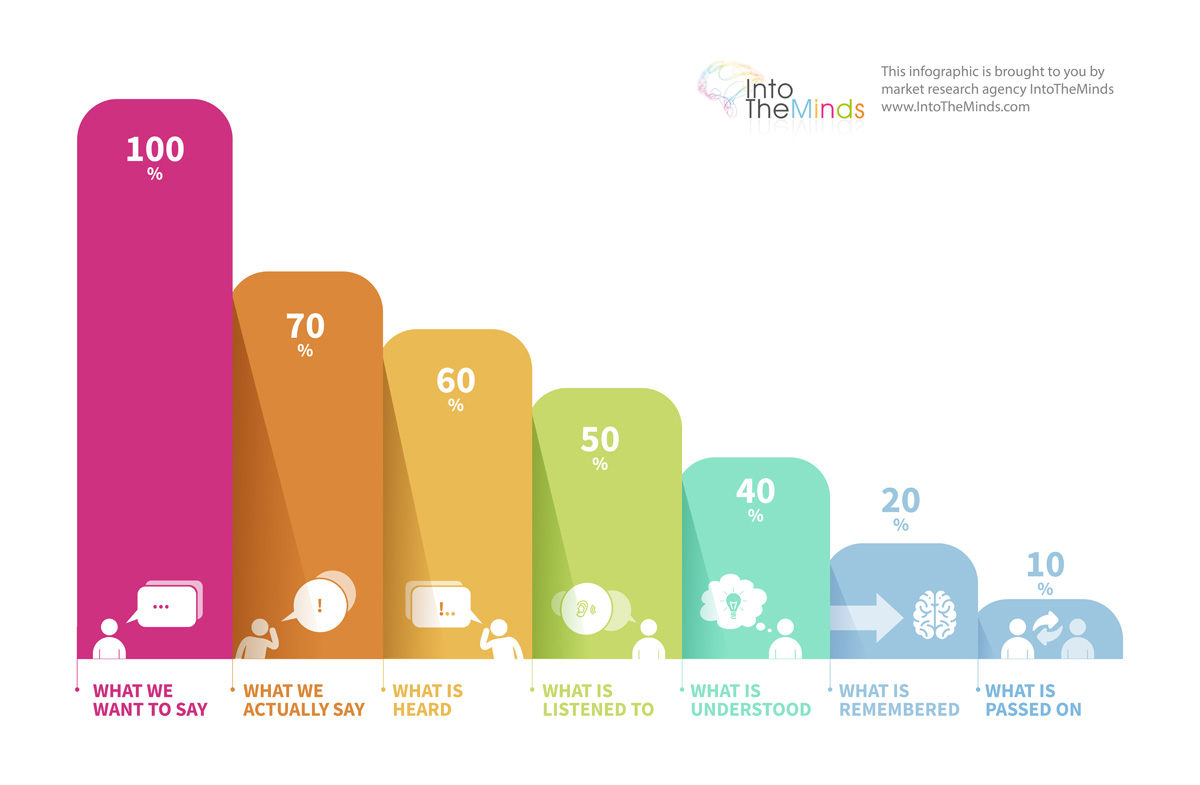

The physical distance that results from the virtualization of interactions seems to me to represent a new kind of communicational bias. With Emmanuel Tourpe’s permission, I have reproduced the text he wrote on the difficulties of communication, cognitive biases and the problem of communicating. The distance imposed by confinement and the use of digital tools seems to me to complicate a little more the search for the intention of the interviewee and of course, the detection of emotions. How, through the filter of the camera, can one detect body signs that betray an unspoken feeling, in short, information that is crucial for any qualitative research of an exploratory nature?

Let us now listen to Emmanuel, who has the rare gift of writing clearly while preserving the beauty of the language. Don’t hesitate to consult his course on communication theory.

“To communicate is to get a message across despite the 27 usual cognitive biases (or wounds of intelligence) that confuse it and obscure meaning.

This requires an effort on the part of the communicator (expressis verbis: clarity and sharpness). But above all, on the part of the one who receives the message: the intentio auctoris (actively seeking what the other wants to say).

Everybody knows that there are a set of rules to get your message across.

But we often forget that there is a real job to be done by the receiver. Be attentive only to the perceived emotions or instinctive feelings one feels, born of the message; project one’s “a priori”; not pay attention to the context; lend intentions; do not read or hear what is said or written.

There is a responsibility, rarely emphasized, on the part of the receiver: to seek the author’s intention.

It’s a rule in scientific exegesis – it should be a rule in couples, families and at work. Instead of diving into what I think I understood – having a passion for thinking about what one wanted to express.

When someone speaks to us or writes to us, it is our whole existence with its wounds that interprets the message – and more often than not misinterprets it. Reason and love must prevail here over emotion to recover the authentic meaning of the author. This is a forgotten rule of communication if we took advantage of the time of confinement to sharpen our sense of active reception, and to communicate better also by “saving the proposal of others” (St. Ignatius) instead of throwing ourselves on everything that is said without listening or effort…”.

For further information

Hall, S. (1973). Encoding and decoding in the television discourse.

Ide, P. (1992). Connaître ses blessures. Ed. de l’Emmanuel.

Illustration images: shutterstock

Posted in Marketing.