What will be the impact of Covid-19 by sector of activity? To answer this question, we rely on the different sectorial analyses we have produced. In the article below we present a concise synthesis of the impact of COVID for each sector of activity. To know in detail the effects of COVID on the sector in question, you will find at the beginning of the paragraph the link to the complete analysis.

Sommaire

- Introduction

- Impact of COVID by sector

In a nutshell

Our analyses of the impact of Covid-19 by sector of activity show that all sectors are impacted to varying degrees. Very few will come out of it positively.

The pure online players are the only ones who limit the damage. Streaming sites, for example, have seen their subscriptions increase, e-commerce food players see their business accelerate, the online advertising market is recovering since the end of April 2020. If there was only one thing to remember is that those who do not master the codes of online business will disappear. We are going to see a mass extinction of 1.0 businesses.

Introduction

The Covid-19 crisis led to significant behavioural changes. On the one hand, consumers have altered the way they buy or have been forbidden to buy. On the other hand, companies have frozen their budgets and avoided taking any risks whatsoever. These two factors alone explain many of the impacts of COVID on different industries.

We are going to see a mass extinction of businesses 1.0

Impact of the COVID on the aviation sector

Impact of the COVID on the aviation sector

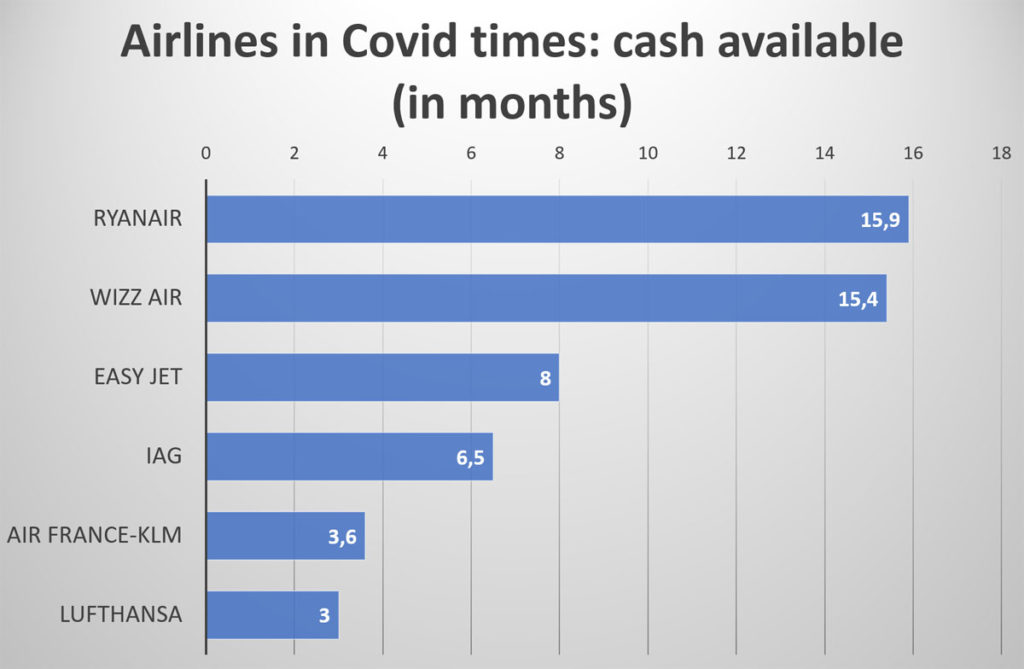

Our full analysis of the impact of COVID on the airline industry was published at the beginning of the crisis.This sector is one of the most affected of all by COVID. It is a convergence of factors that explains it. First of all, the airline sector is inherently fragile: operating margins have always been thin, and there has always been a lot of restructuring. The post-2008 growth period made us forget this. Still, it has never been easy to make a place for ourselves in this market where the aircraft load factor determines profitability (minimum 75%, sometimes 80% on specific highly competitive destinations). The fixed costs to run an airline are gigantic, and the COVID crisis has therefore melted the cash flow of airlines. As we have shown in our analysis, those that are best equipped to resist are low-cost airlines. Ryanair, for example, has 15.9 months of cash at its disposal (see table below).

The need for funding forces the big companies, who have set themselves up as national flagships, to ask for help from the States to survive and to take radical decisions. Ryanair (1st European company with 150m of passengers transported in 2019) announced, for example, to lay off 3000 people (but without calling for state aid and we can count on it, after having been attacked by the traditional companies, not to make any quarter). But not everyone can be saved. The smallest actors should, therefore, go bankrupt. We should logically, therefore, see a consolidation of the market around the big national companies on the one hand, and the most solid low-cost players on the other. In the United States, only three large companies (Delta, United, Southwest) are likely to survive in the long term.

From an operational point of view, the low fill rate will lead to the closure of direct lines. These closures are expected to multiply over the next 12 months as customers, scalded by the health crisis or banned from travelling beyond certain borders, will turn away from specific destinations. As a result, hubs, those large airports that connect one plane to another, are expected to become increasingly important. They are the ones that will concentrate on departing passengers to achieve a suitable load factor. This concentration effect will bring its share of challenges in the short term since a minimum social distance will have to be maintained at all times. Airport facilities will, therefore, be developed to manage passenger flows at the various points of concentration (check-in, controls, boarding).

In conclusion, the impact of COVID on the airline industry will be significant because it is the result of the convergence of unfavourable factors: high fixed costs, profitability that imposes concentration of individuals (in airports, in aircraft), a restriction or even a ban on travel. The impact of COVID on the airline industry will be felt for many years, and a return to normal cannot be expected before 2022.

Impact of COVID on the food retail sector

Impact of COVID on the food retail sector

Our analysis of the impact of COVID on the retail food sector was carried out at a time when the first structural measures were being put in place to guarantee customer safety.

The period of confinement highlighted new types of behaviour in supermarkets. Customers spend 49% more per minute spent in the supermarket. Logically, retailers’ turnover has soared, but profitability will not follow the same curve in the coming months. Indeed, costs (logistics, human, operational) are much higher than before (up to £925m for Tesco). Above all, consumers have turned to essential products (flour, yeast, pasta, rice, and so on) to the detriment of those on which margins are highest. Supermarket journeys (see illustration below) have become longer, more efficient, leaving less room for the impulse purchases that are so important for retailers.

The massive use of the Internet has accelerated the transition to e-commerce, whose market share is expected to increase by 2-3 percentage points in 2020. This massive transition has been painful as supply chains have not kept pace. The preparation of orders (drive or click-and-collect) is done manually, which represents a significant obstacle. We can, therefore, expect, between now and 2022 (sooner if new pandemic waves hit Europe), automation projects (so-called “picking”) to come into being. This will lead to a re-centralisation of order picking. This centralisation will pose new problems for vast territories such as France, Germany or the United Kingdom. In these territories, a hybrid model will develop; the centralisation of order preparation for densely populated (urban) areas, and the decentralisation (on-site preparation) for rural areas.

Finally, during this crisis, there has been a renewed interest in local shops (+26%) and organic products (sales 20-30 percentage points higher than for conventional products). This revitalisation of local shops and the promotion of quality products bodes well for the future. Town centres need to find a new lease of life. But the big question here is whether this trend will continue. Indeed, with a temporary unemployment rate of 25%, consumers are going to cut back on their spending sharply. This reduction will affect non-essential purchases, but also food. The polarisation of consumption is likely to increase. On the one hand, as the middle class becomes poorer, it will turn to more basic and lower quality products. On the other hand, the more affluent will increase their consumption of quality products.

Impact of COVID on the non-food retail sector

Impact of COVID on the non-food retail sector

In our analysis of the impact of COVID on the non-food retail sector, we highlighted the immediate financial effects of the closure of these businesses. At the time of writing, many of them have still not reopened. Their situation is extremely precarious, forcing the public authorities to come to their rescue. However, the postponement of charges, loans, and so on, will not be enough to save them all. 25% of small businesses may not survive the crisis. One thing is sure, however: they will all have to adapt to face the changes that will continue over the next few years.

Ensuring customers’ safety will be a condition to do business. The solutions devised by food retailers will be taken up (see the example of the airlock invented by Carrefour to decontaminate customers at the entrance to the store). Flow management solutions will also be developed in parallel with the reduction in the number of customers at the point of sale. This will not encourage offline sales, which is why retailers will have to convert to e-commerce very quickly. Retailers (even the smallest) who do not have an e-commerce site by 2021 will be in great danger. It is a priority to understand that an e-commerce site is a survival factor in 2021.

Ensuring customers’ safety will be a condition to do business. The solutions devised by food retailers will be taken up (see the example of the airlock invented by Carrefour to decontaminate customers at the entrance to the store). Flow management solutions will also be developed in parallel with the reduction in the number of customers at the point of sale. This will not encourage offline sales, which is why retailers will have to convert to e-commerce very quickly. Retailers (even the smallest) who do not have an e-commerce site by 2021 will be in great danger. It is a priority to understand that an e-commerce site is a survival factor in 2021.

For retailers specialising in durable consumer goods, we are betting on virtual reality. We believe that in the future, it will make complex purchases (think of a kitchen, for example) more manageable, and limit the number of visits to the sales outlet and the number of returns. It remains to be equipped because despite a surge in helmet sales, the equipment is still expensive and the applications are still not very widespread. The Covid-19 crisis could well give a boost to this technology, which has been vegetating for several years.

Regardless of the sector, Covid-19 will force retailers to rethink their customer experience. The crisis will have had a lasting impact on consumer morale (not to mention the disastrous economic outlook), and there will be a need to provide authentic customer experience, full of values that to which consumers can relate. It will also be necessary to ensure that we have staff who communicate positive energy and emotions to customers. We believe that consumers will go for brands that are good for them first.

The impact of COVID on the media sector

The impact of COVID on the media sector

Our analysis of the impact of COVID on the media sector shows a paradoxical situation. On the one hand, media consumption has never been so high; on the other media revenues are falling, and media costs are exploding. Advertising revenues are in fact in freefall and will plummet by 10% to 20% in 2020. The decrease over March to May 2020 has been 50% on average and has sometimes reached 99% for media such as billboards or cinema. For broadcasters, the loss of earnings amounts to tens of millions of Euros. The increase in consumption of online media has had significant repercussions. Streaming sites have had to limit their transmission speed. Broadcasters offering OTT platforms have seen their traffic increase by 50%. The costs associated with the increase in bandwidth have been significant. It can be estimated that for every additional euro spent on infrastructure costs, €5 of advertising revenue has evaporated.

For every additional euro spent on infrastructure costs, €5 of advertising revenue has evaporated

This daunting equation explains the restructuring plans that are being put in place just about everywhere. Smaller players (regional dailies, for example) that have not been able to take the digital turn may not recover.

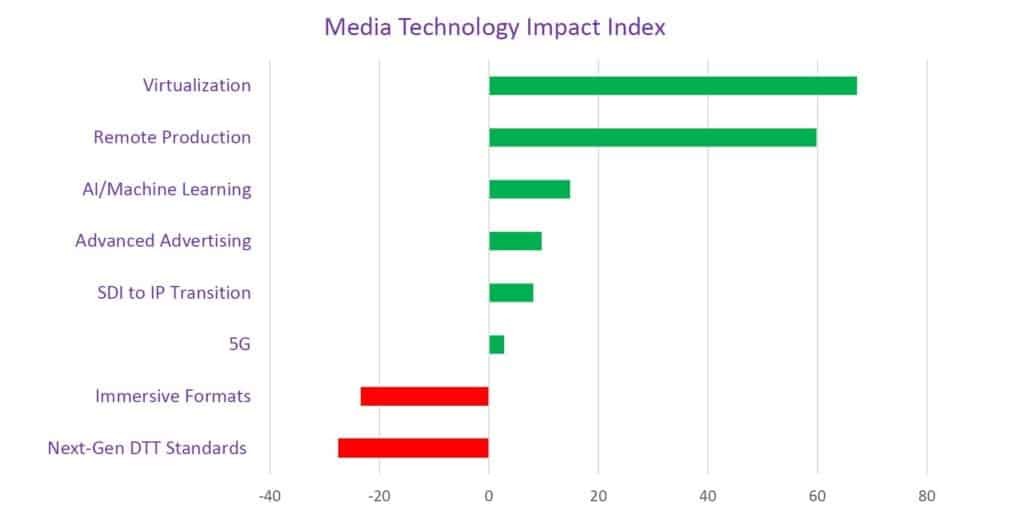

Of course, all the media are waiting for a recovery in economic activity to regain liquidity and stop the haemorrhage. But we doubt that the appetite of advertisers will be restored any time soon. It is reasonable to estimate that the impact of the COVID on the media sector will be aggravated by a period of sluggish demand until September 2020. In the meantime, strategic decisions will be taken that will affect staff as well as technology investments. Investments in IT asset management and virtualisation will be essential. This will be at the expense of other technologies which will be relegated to second place (see results of the IABM study below).

The main winners of the Covid-19 crisis are the streaming sites: Netflix and Disney+ in the lead. Netflix has wholly relaunched itself and has attracted an unprecedented number of new subscribers (more than 17 million) while Disney+ has passed the 50 million subscriber mark 2 years ahead of schedule. This tidal wave is driving consumption in streaming and should be a wake-up call for traditional broadcasters. The formation of international platforms is essential to resist. Regional or national alliances are no longer sufficient. Content from different sources must be combined, whatever the origin: first in one language, then by offering (as Arte does) translations.

The main winners of the Covid-19 crisis are the streaming sites: Netflix and Disney+ in the lead. Netflix has wholly relaunched itself and has attracted an unprecedented number of new subscribers (more than 17 million) while Disney+ has passed the 50 million subscriber mark 2 years ahead of schedule. This tidal wave is driving consumption in streaming and should be a wake-up call for traditional broadcasters. The formation of international platforms is essential to resist. Regional or national alliances are no longer sufficient. Content from different sources must be combined, whatever the origin: first in one language, then by offering (as Arte does) translations.

The impact of COVID on the advertising industry

The impact of COVID on the advertising industry

In our dossier on the impact of COVID on the advertising industry, we highlighted the very worrying situation in the sector. The decline in revenue is 50% for the agencies the most unscathed, and 90% for those that were less fortunate. This can be explained by the fact that 75% of advertisers have reduced (or stopped, like Coca-Cola) their advertising investments. Coca-Cola’s explanation for this radical decision is fascinating: there is no return on investment for advertising in such a context. However, we can see that some local media (daily newspapers) have seen a resurgence of advertising in April. But this effect can be misleading because, as our analysis shows, the advertising messages have changed completely. It is no longer a question of selling a product, but of “saying thank you”, of displaying values. So, we are no longer in the business of selling but in the construction of a brand identity.

More than ever, local anchoring and the search for values that will resonate in the hearts of consumers are more than ever the priority. But this is being done on a shoestring budget. We are talking about campaigns launched with funds divided by 10 or 20. No more advertisers dare to speak up to sell, let alone commit to the medium term. Campaigns are therefore postponed most of the time, waiting for better days. The work remains vital in the agencies, but there are no more new projects. Agencies have reduced to 3/5 for the most part and redundancies will be on the list over the coming months. It is indeed illusory to think that the market will recover quickly. A gradual recovery from September onwards is the most commonly envisaged option.

Illustrations : shutterstock, amoobi

Posted in Marketing.