Working from home became the norm during the COVID crisis. But it doesn’t only have advantages. The transition to 100% homeworking mode, dreamed of by some, would be a disaster for innovation.

If you only have 30 seconds

- The concentration of individuals in one place is correlated with the capacity for creation and innovation.

- Informal contacts are essential to build the capacity to recombine information and lead to innovation.

- Teleworking prevents informal contacts and slows down the emergence of innovative ideas.

- Disseminating an innovative idea requires convincing skills. These skills are based in part on the transmission of non-verbal emotions.

Summary

- Introduction

- The link between individual concentration and innovation

- The importance of networks for innovation

- Physical presence and innovation

- Psychological impact of homeworking

- Conclusion

- Sources

Introduction

To show the shortcomings of working from home from a company innovation perspective, I will proceed as follows. I will first show that innovation is a collective process. In order to stimulate, it is necessary both to concentrate individuals and to encourage their interactions. Secondly, I will show that to flourish, innovation needs a positive environment, and I will establish that home working has effects that are opposed to the pursuit of this objective.

To avoid criticism from supporters of home-working, I would like to make it clear from the outset that this demonstration is only valid for 100% home working, that is to say, a completely nomadic way of working.

The concentration of people is essential for creativity and innovation

In his work, Geoffrey West demonstrates that cities are like living organisms. They follow the same biological rules and have economies of scale for everything but creativity. Creativity “accelerates” with the size of cities. In the words of neuropsychiatrist Boris Cyrulnik: “Our brains are fundamentally built to be connected to other brains.”

Our brains are fundamentally built to be connected to other brains

Boris Cyrulnik

Before him, in the 1990s, the Japanese Nonaka developed the SECI model (Socialisation, Externalisation, Combination, Internalisation) to explain the creation and dissemination of knowledge. He shows that new knowledge does not only come from the thoughts of a single individual (the myth of the isolated visionary). Communication within the company is, in fact, crucial for innovation. As Tsuji et al. (2019) wrote, “managers need to understand the benefit of face-to-face communication, as it concerns not only individuals but also the capacity and productivity of the entire organisation”. (“executives have to understand the benefit of face-to-face communication because it affects not only individuals but also the capability and productivity of the entire organisation”).

Networks are essential for innovation

Steven Johnson confirms Nonaka’s model in his book “Where good ideas come from: a natural history of innovation” (summary available here). Good ideas are not born in the head of an isolated individual. On the contrary, good ideas are the result of interactions with the outside world, more precisely social interaction. Steven Johnson distils through his book this recurring idea that flashes of inspiration, these “eureka” moments as they are called, very rarely occur when one is alone in one’s laboratory (or office). Ideas are born from conversations, especially informal ones, with other people, colleagues, friends and relatives. In this article, you will find more examples of the multiplier effect on innovation of bringing together fertile minds. This network effect is reminiscent of the role of “weak links” in inhibiting filter bubbles.

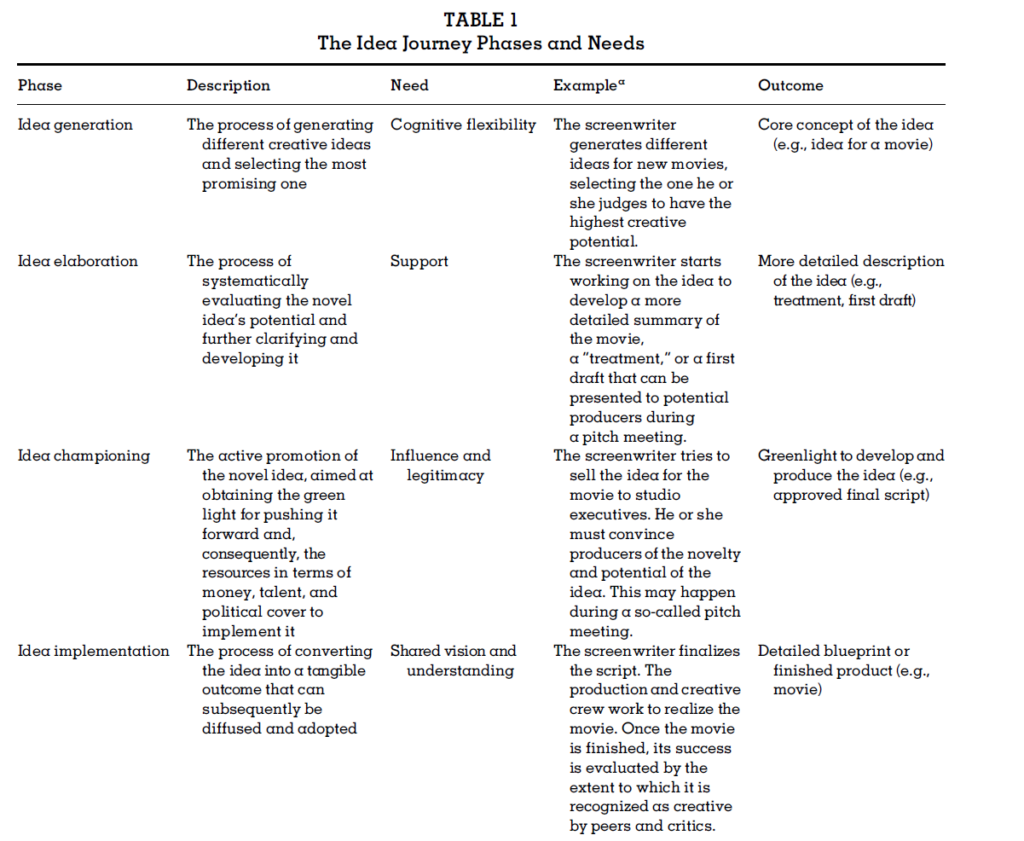

The network effect on the innovation process is also highlighted by Perry-Smith and Manucci (2017). The authors divide the innovation process into 4 phases (see table below):

- the generation of the idea

- the development of the idea

- the promotion of the idea

- the implementation of the idea

In each of these phases, the role of interactions within a (corporate) network is essential.

In phase 1 (the generation of the idea) the cognitive flexibility of the individual and his or her ability to combine elements from different domains play a significant role. The interactions enable the individual to acquire information that he or she can then use, sometimes decades later. This is what Steven Johnson calls the “possible adjacent”, this linking of distant elements, seemingly unconnected, by an individual.

In Phase 2, social interactions are also essential. The isolated individual is no longer on the move because it is a matter of maturing the basic idea of improving it.

Phase 3 is only a sequence of interactions since it is necessary to convince and promote the idea. Communicating your enthusiasm is essential to convince your audience. And this can only be done with the awakening of the 5 senses.

From 2017 IBM has recalled its employees to the office with the ambition to accelerate the pace of work and innovation.

You have to be physically present for the innovation process to move forward

From the previous paragraphs, it is clear that physical interactions, on the one hand, and informal contacts on the other, are factors that contribute to innovation. It is, therefore, necessary to consider the impact of home-working on these two factors. Informal contacts are a catalyst for change because they allow the linking of distant ideas and needs. The question to be asked here is: is it possible to have the same level of informal interaction in home-working as in face-to-face work? It appears that some companies, by no means the least, have already experimented with home working on a large scale and have drawn conclusions that we would do well to bear in mind.

In a great burst of enthusiasm, home working theorists have been extolling the virtues of the COVID crisis. Home-working would have only positive aspects. Managers, who up until now had been concentrated in the cities, dream of a life in the country, and a relocated professional activity. The extensive use of teleconferencing solutions would have proved the uselessness of travel and physical presence in the office. While the advantages are well perceived by employees (cf. Marshall-Cam, 2019), some disadvantages should not be overlooked. It is also ironic to think that large companies did not wait for the COVID crisis to test home working and then back down. Thus, already in 2018, IBM rediscovered the virtues of face-to-face work. An article in the Wall Street Journal thus echoes a widespread back-pedalling: “Managers say that placing workers in the same physical space speeds up the speed of work and spurs innovation. Yahoo had already begun a similar move back to the office in 2013.

The psychological impact of homeworking

Finally, being creative requires that the climate be conducive. When the environment is anxiety-provoking, stressful, cognitive abilities are all focused on other processes. And these processes are not compatible with the serenity required for innovation. Generally speaking, we have seen that the COVID crisis has substantially raised the anxiety level of populations. The psychological impact of home-working is not insignificant, either.

A study such as that of Tsuji et al. (2019) shows that physical interactions make it possible to preserve one’s psychological capital. These interactions, real and not virtual, contribute to the employee’s well-being. This result is echoed in the study by Marshall-Camm (2019, pp.133-134). The author studied the implementation of home-working in a department of the English civil service. She points out, in line with other studies (Forester, 1989; Mokhtarian et al., 1998; Wilton, Páez & Scott, 2011), that isolation (at home) is a factor that motivates employees to return to the office.

Home-working, therefore, has psychological effects which are far from insignificant and which further inhibit the innovative capacity of individuals and the company as a whole.

Conclusion

The COVID crisis has accelerated the acceptance and transition to homeworking. The employees, seduced in the short term by this new way of working, are in favour of it. While these forms of implementation may differ substantially (from part-time to full-time home-working), the negative consequences on the company that distance between employees can have, are not to be overlooked. By making informal contacts between employees less frequent, by suppressing the use of individual senses in communication, home-working represents a risk for the innovative capacity of companies. Ideas are indeed born, developed and implemented by taking advantage of informal contacts between employees, and by activating the network thus formed within the company.

Sources

Cyrulnik, B., Bustany, P., Oughourlian, J. M., André, C., Janssen, T., & Van Eersel, P. (2012). Votre cerveau n’a pas fini de vous étonner: entretiens avec Patrice Van Eersel. Albin Michel.

Marshall-Camm, J. (2019). A critical reflection on the introduction and implementation of a homeworking policy in a United Kingdom government department (Doctoral dissertation, Lancaster University).

Perry-Smith, J. E., & Mannucci, P. V. (2017). From creativity to innovation: The social network drivers of the four phases of the idea journey. Academy of Management Review, 42(1), 53-79.

Simons, J. (2017). IBM, A pioneer of remote work, Calls workers back to the office. Wall Street Journal.

Tsuji, S., Sato, N., Yano, K., Broad, J., & Luthans, F. (2019, October). Employees’ Wearable Measure of Face-to-Face Communication Relates to Their Positive Psychological Capital, Well-Being. In IEEE/WIC/ACM International Conference on Web Intelligence-Companion Volume (pp. 14-20).

Images d’illustration : Shutterstock