![Customer experience: definition, measurement, analysis [Guide, 2021]](https://www.intotheminds.com/blog/app/uploads/marketing-study-customer-experience-scale-TN.jpg)

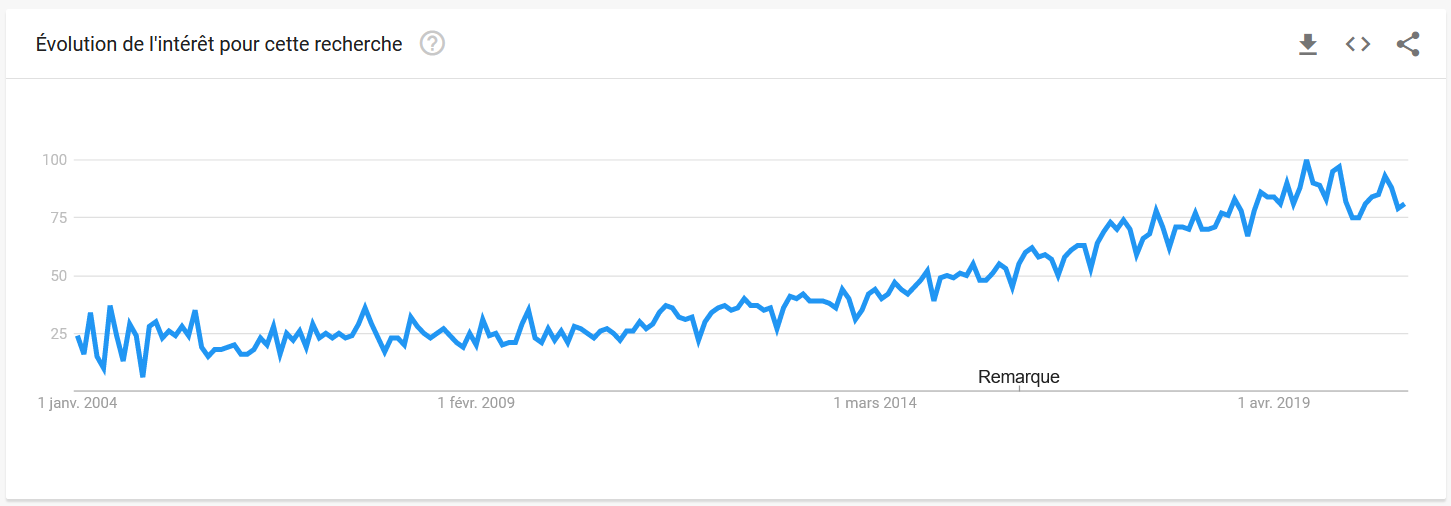

The customer experience has become an almost magical expression that is synonymous with marketing success and brand differentiation. But what is the reality behind the customer experience? While most non-specialists confuse customer experience with customer satisfaction, this guide takes stock of a concept evolving steadily since its invention nearly 40 years ago.

Summary

- Definition of the customer experience

- Customer experience: more than 40 years of history

- Understand the foundations of the customer experience

- Impact of customer experience on marketing practices

- Retail and Customer Experience

- Customer Experience Analytics Grid n°1

- Customer Experience Analytics Grid n°2

- Customer Experience Analytics Grid n°3

- 3 ways to measure customer experience

- Sources

Customer experience: Definition

As we will see in the paragraph devoted to the history of customer experience, this framework’s definition has evolved. Today it is accepted to define the customer experience as a multidimensional structure that encompasses the cognitive, emotional, behavioural, sensory and social responses to a company’s commercial offer throughout the entire customer experience.

In other words, the customer experience is a consumer perception that affects several dimensions:

- the cognitive dimension: how the consumer thinks, reasons, about the brand and its products. What are the mental images that emerge when the consumer thinks about the brand?

- the emotional dimension: the messages sent by the brand arouse emotions which in turn will influence …

- the behavioural dimension: that is to say, how the consumer reacts to the stimuli sent by the brand through its various points of contact (or touchpoints)

- the sensory dimension: the consumer’s senses can be solicited in different ways (visual, olfactory, tactile, gustatory, auditory) which can provoke more or less positive reactions.

- the social dimension: perception of the company or brand is influenced by its external environment, online or offline. Opinions and comments are all ways of exchanging around a brand that can change your perception of it.

What is a construct, and why is it necessary to define it?

In many situations in the humanities and social sciences, one seeks to study hypothetical entities, which result from a theoretical elaboration (or construction): intelligence, skills, knowledge, competencies, abilities and various abilities, motivation, interest, attitudes. These entities (precisely called “constructs”) are not directly accessible to observation and measurement. Therefore, it is possible to study them only from the manifestations they are supposed to produce or make possible (generally behaviours).

Source: IRDP

What people really desire are not products but satisfying experiences.

Lawrence Abbott (1955)

Customer experience: a 40-year history

Customer experience is the “modern” name for a construct anticipated more than 40 years ago. As early as 1955, Abbott wrote:

“What people really desire are not products but satisfying experiences”.

The construction of modern marketing from the 1960s onwards laid the foundations for the customer experience by highlighting essential themes in each decade:

- purchase decision models (1960-1970)

- customer satisfaction and loyalty (1970)

- quality of service (1980)

- relationship marketing (1990)

- customer relationship management or CRM (2000)

- customer focus or “customer-centricity” (2000-2010)

- Customer Commitment (2010)

The turning point in the customer experience came in 1982. That year Morris Holbrook and Elizabeth Hirschman published a seminal article entitled “The Experiential Aspects of Consumption : Consumer Fantasies, Feelings and Fun”. The former was a professor at Columbia University, the latter at the University of New York. So, 40 years ago, we were talking about consumer experiences. The filiation with the customer experience and therefore, apparent when they wrote:

Finally, by experience, I mean that consumer value resides not in the product purchased, not in the brand chosen, not in the object possessed, but rather in the consumption experience(s) derived therefrom [. . .] In essence, the argument in this direction boils down to the proposition that all products provide services in their capacity to create need- or want-satisfying experiences [. . .] In this sense, all marketing is “services marketing.” This places the role of experience at a central position in the creation of consumer value.

Generally speaking, the customer experience is therefore placed in the more general context of service marketing. This prefigures the revolution brought in 2008 by Lush and Vargo in their founding article “Evolving to a new dominant logic for marketing“.

Taking a global perspective on the subject, Chaney et al. (2018) attribute to Holbrook and Hirschman 3 crucial changes:

- redefinition of conceptual frameworks in marketing

- renewal of methodological tools

- managerial interest in this new material

It remains to be seen how the popularisation of the customer experience as a management tool has occurred. It would be presumptuous to want to retrace such a convoluted path, but Bernd Schmitt’s work is no doubt not unrelated to it. In 2003, Schmitt (also based at Columbia University, not far from Holbrook’s office) published a book for the general public entitled “Customer Experience Management: A Revolutionary Approach to Connecting with Your Customers”. It was this book that also popularised the CEM acronym for “Customer Experience Management”. This book was itself a follow-up to another title, also very popular, published in 2000 by the same author: “Experiential Marketing: To Get Customers To Relate To Your Brand”.

We must admit that before 2000 the term “customer experience” was not very popular. A search on Google Scholar tells us that this term was only used 18 times in the title of scientific publications between 1980 and 2000.

The renewal induced by the concept of customer experience has not only been theoretical. It has also been methodological. Recognising that consumer choices can be subjective and that emotions play a role; marketing research has become increasingly interested in qualitative methods. The rise of digital experiences has led to the birth of netnography, the use of ethnography in online communities.

Understanding the fundamentals of the customer experience

We can sum up the customer experience in 2 letters (CX) for the initiated; it is not useless to go back to this concept’s very foundations to understand its essence.

Before Holbrook and Hirschman, the consumer was seen as a rational economic operator. This means that all marketing theories before 1982 assumed that the consumer made conscious choices to maximise satisfaction. It is this rationality, this conscious objectivity that Holbrook and Hirschmann questioned with the 3 F’s: “fantasies”, “feelings” and “fun”. In other words, Hirschmann and Holbrook’s intuition is that there are consumer choice processes that favour subjective aspects whose dynamics are far removed from the simple maximisation of economic advantage. Customer satisfaction is, therefore, no longer limited to the equation “economic costs/benefits”. It involves emotional aspects without really knowing why. You will note that we have not talked about irrationality because these emotional aspects are entirely rational. The consumer prefers, sometimes unconsciously, to maximise those aspects of the offer that give him pleasure beyond the satisfaction provided by the product or service consumed.

What is the link between customer satisfaction and customer experience?

On many websites belonging to companies selling online questionnaire solutions, experience measurement is confused with customer satisfaction measurement. Let’s be clear. Measuring customer experience has nothing to do with measuring customer satisfaction. If you think that a Net Promoter Score (NPS) measurement will allow you to measure customer experience, you are wrong. You will find explanations on how to do this in the “measuring customer experience” section.

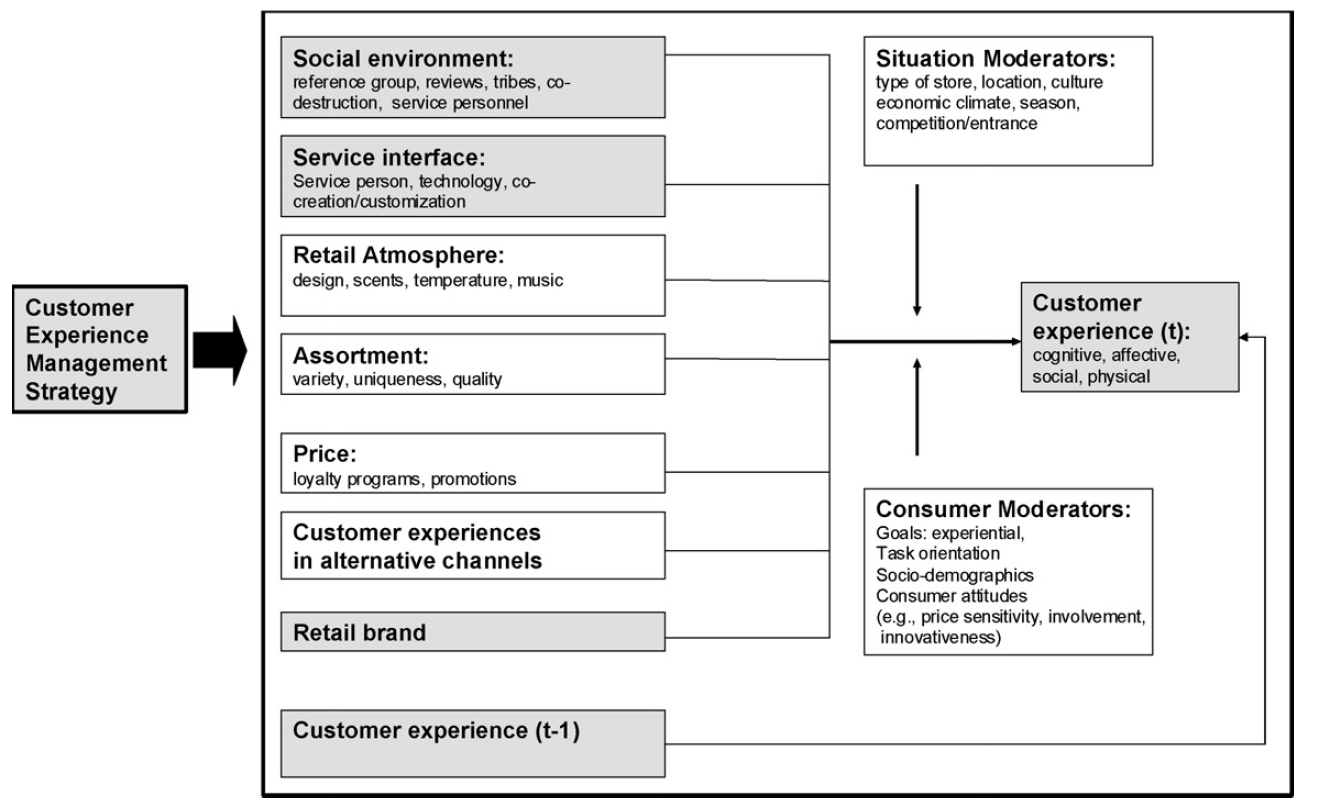

The key point raised here is the customer experience dimensions (which we will address in more detail in the measurement section). At this stage, it is fundamental to understand that the concept of client experience is both conscious and unconscious, both cognitive and emotional. This was a conviction of Holbrook and Hirschmann as early as 1982, which would be developed by Verhoef and his colleagues in 2009 in an article that was a new starting point for customer experience research. They described customer experience in retail as:

holistic in nature and involve[s] the customer’s cognitive, affective, emotional, social and physical responses to the retailer. This experience is created not only by those factors that the retailer can control (e.g., service interface, retail atmosphere, assortment, price) but also by factors outside of the retailer’s control (e.g., the influence of others, the purpose of shopping).

Impacts of the customer experience on marketing practice

Beyond a conceptual and theoretical revolution, the customer experience had very early on, real impacts on companies’ marketing practices. We could sum up this impact by saying that the birth of the concept of experience provided an answer to companies seeking to build an offer based on non-functional dimensions. When formulated differently, the customer experience is the reference framework which, at the turn of the 2000s, enabled companies to organise disparate marketing actions which aimed to promote aspects other than the simple use of a product or service. This transitional stage was essential to articulate the company’s differentiation strategy.

There is much to be said for the impact of the customer experience at all levels of marketing. But in the end, it all boils down to two very distinct fields of action. The first is strategic marketing; the second is operational marketing.

Branding

Branding has been primarily affected by the customer experience as it has redefined the contours of the company’s strategic mission. We have moved from transactional to experiential objectives. As a result, branding is no longer seen as the entity that must provide the products or services that maximise customer satisfaction. The brand becomes the embodiment of values and emotions that must be brought to life at the various touchpoints with the customer. This necessity is dictated by the need to build customer loyalty.

Customer relations

We must, therefore translate efforts made in upstream branding into downstream efforts to build customer loyalty. This is the task of operational marketing. According to Fournier (1988), the relationship between the consumer and a brand evolves as marketing actions evolve. Fournier explains that the customer’s representation of the brand influences his relationship with it. The link with loyalty is, therefore established.

Customer experience in the retail sector

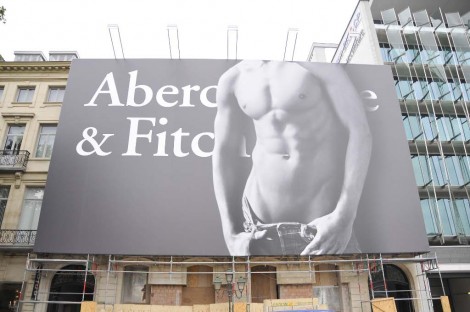

The notion of customer experience remains intimately linked to the world of retail. The reason for this is simple: it is the sector of the economy with which consumers are most in contact. It is, therefore, the sector that has the greatest need to build loyalty. The battle to differentiate oneself is consequently a tough one, and for the past 20 years, it has been fought in the field of customer experience.

This battle first materialises through the creation of retail environments of a new nature. There is talk of flagship stores, “brand museums” that are all concrete emanations of the brand’s celebration. Since the brand’s values and emotions are an axis of loyalty, we must materialise them in spaces where the customer can meet them. This is the role of these new retail formats which, for some, sell nothing. Kotler is not mistaken, since he too had intuition as early as 1973 of the retail environment’s importance as an axis of differentiation in an article he published in the Journal of Retailing. He then talks about the concept of “atmospherics” that could be assimilated to the sales outlet’s atmosphere.

Without a quality product, customer experience is a futile strategy.

In addition to these particular retail formats, the customer experience has, of course, also moved to the traditional sales outlets. This is where it is most commonly found, perhaps to such an extent that “shop” and “customer experience” have become the other side of the same coin. How can this strong link be summed up without falling into anecdotal details? There are, of course, many analytical frameworks for customer experience in sales outlets. Still, I like to think that it all boils down to 2 elements: a tangible and intangible.

The tangible element: what’s around the product

The customer experience is first of all instilled by what is around the product on sale: the sales outlet itself (its layout, design, concept) but also, literally, what is around the product (packaging, label, and so on). Each tangible, material aspect is a source of interaction and can trigger stimuli affecting the 3F’s: “Fantasy”, “Feelings”, “Fun” (Holbrook and Hirschmann, 1982).

The intangible element: interactions

The other major part of the customer experience, which is too often forgotten, relates to customer interactions. This is the intangible part of the customer relationship, which can trigger both the most positive (enchantment) and the most negative emotions.

You may have noticed that I did not mention the “product” above. I did it on purpose because, without a quality product, the customer experience is a futile strategy. Having products that satisfy the customer is, therefore, a prerequisite.

Concept stores, a materialisation of the advent of the customer experience

Concept stores are a tangible materialisation, in the retail world, of the desire to create a memorable customer experience. The concept store is the place where new elements collide and create surprise and astonishment. Over the years, we have discovered many of these, which we have documented in a map form.

In their 2009 article, Verhoef and colleagues propose a scheme that considers the complexity of the customer experience concept. It shows that the company only partially influences the customer experience because it depends on factors that for some people are beyond control: social environment, customer experience before the purchase, conscious and unconscious goals of the consumer, perceptions (cognitive, emotional, social, physical) of the customer in the sales outlet.

Therefore, each of these aspects constitutes a focus of work in terms of Customer Experience Management (CEM).

Customer Experience Grid by Bernd Schmitt

In his book “Customer Experience Management” (2003), Bernd Schmitt proposes an analysis of the customer experience in 4 “layers”:

In his book “Customer Experience Management” (2003), Bernd Schmitt proposes an analysis of the customer experience in 4 “layers”:

- product or brand experience

- experience at the product category level

- situation of consumption and use

- business and socio-cultural context

This way of looking at the customer experience “in layers” is interesting. It is semantically quite similar to the research on market levels. If we compare Schmitt’s “layers” in 2003 and Verhoef’s framework in 2009, we can see that the two readings are not opposed. We can easily place many (if not all) of the influencing factors proposed by Verhoef in one or the other of the layers suggested by Schmitt. This is reassuring.

Grid for the sensory reading of the customer experience

Since the customer experience is about creating (positive) emotions that will foster brand loyalty, it is essential to focus on the senses. The 5 senses are indeed emotional vectors. Thanks to them, emotions can be permanently anchored and mobilised at will. Everyone has already experienced a situation in which a smell, a sound or a taste has brought back a specific memory. This synaptic association, anchored deep within us, offers brands the opportunity to move the customer experience from the intangible (a sensation evoked by the mobilisation of a sense) to a memory. It is this mechanism that is at the basis of the sensory reading grid of the customer experience.

The sensory reading grid of the experience evaluates how the senses are mobilised when the consumer interacts with the brand. By the very nature of the analysis, you will have understood that this sensory reading grid is above all adapted to “physical” encounters between the brand and the consumer. This analysis consists of analysing each component of the customer experience according to the senses. This reading is not new. Hulten proposed it as early as 2009 in this article.

- olfactory: is an odour present? Is it pleasant? What does it evoke? Does the intensity of the odour(s) cause discomfort to customers?

- auditory: is there auditory stimulation? If so, is it related to the brand’s DNA? Are there several musical “moods”? What is the tempo? What is the volume? Does auditory stimulation represent a nuisance for consumers? What frequencies are used?

- taste: Does the brand stimulate the customer’s sense of taste, for example, by making them taste products or by provoking salivation? What types of taste emotions are aroused?

- touch: How is the sense of touch stimulated? Can the customer touch certain products? Are the textures pleasant? Does product packaging evoke particular tactile sensations? Are tactile sensations linked to the brand’s DNA? Are they about other senses that are mobilised elsewhere?

- visual: what is the level of light intensity? Does light intensity change customer perceptions?

It would be wrong to think that this sensory reading of the customer experience would be limited to the “physical” domain. Online environments can also mobilise senses other than sight, provoking reactions that evoke the senses in question. For example, an image of food can trigger a salivation reflex and bring up memories of taste. For example, Lee et al. (2017) apply sensory marketing principles to a hotel website to stimulate the senses of internet users.

Which brands best manage the customer experience?

While many brands today have the ambition to propose a differentiating customer experience, one has to look to the United States to find the first examples that have served as inspiration for this marketing branch. In his book “Customer Experience Management” (2003), Bernd Schmitt cites brands as diverse as:

- Starbucks

- Southwest Airlines

- Amazon

- Apple

- Whole Foods

We have analysed on our blog 5 brands that create an unforgettable experience. Get inspired by them!

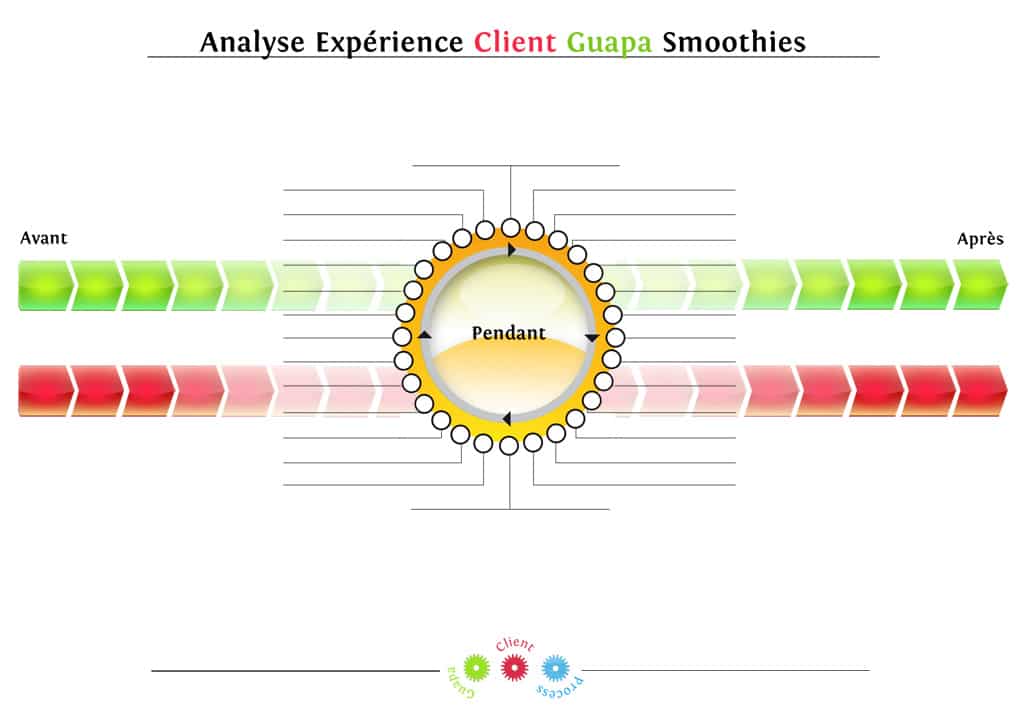

Grid of temporal reading of the customer experience

To map the customer experience, we must first recognise that an experience is not only created at the moment of consumption. In the case of retail, it is wrong to think that the customer experience is only limited to the space of the sales outlet. It is, in fact, much broader than that. It begins long before the actual decision to buy, and continues long after the service or product has been consumed. That is why it is important to represent all the touchpoints between the brand and the consumer.

The rudimentary tool (customer experience wheel) that we developed nearly 10 years ago (see illustration above) allows us to identify the different moments that mark out the customer’s consumption path (you can download this tool free of charge here). Some are important, others are not, but it is essential to make an exhaustive list here. The “customer experience wheel” allows you to read these different moments systematically. The idea is to break down the customer’s journey into distinct moments and be able to rate each of them according to the satisfaction the customer derives from them. The above example was made for a juice bar.

How can the customer experience exist after the act of consumption?

Don’t think that the customer experience stops after the purchase or consumption of the product or service. Because of the emotions aroused, because of the memory that is left, the customer experience can last for a long time and even involve brands and products that no longer exist. This is called nostalgia. This powerful feeling is also used to launch very successful marketing campaigns. The other phenomenon that can occur long afterwards is regret. Regret can work in two directions: remorse for having bought; regret for not having bought. The mechanism of regret formation is linked to the comparison that the consumer makes between a situation at time t, and a situation he experienced at time t-1.

How to measure customer experience?

Improving customer experience involves identifying weak points. And to do so, we need to measure them.

In this section, we will explain how to measure customer experience. Unfortunately, the Internet is full of fake experts who promote their tools and therefore provide false information. In this section, we will focus on scientific research and proven measurement scales.

In an article publié en 2016, Lemon & Verhoef insist that customer experience should primarily be measured globally without a confirmed scale. In particular, they advise implementing proven indicators such as the SERVQUAL scale to measure service quality or the NPS (Net Promoter Score) to measure overall satisfaction. However, they advise against using the CES (Customer Effort Score), which is not a transversal measure and only concerns one aspect of the customer experience.

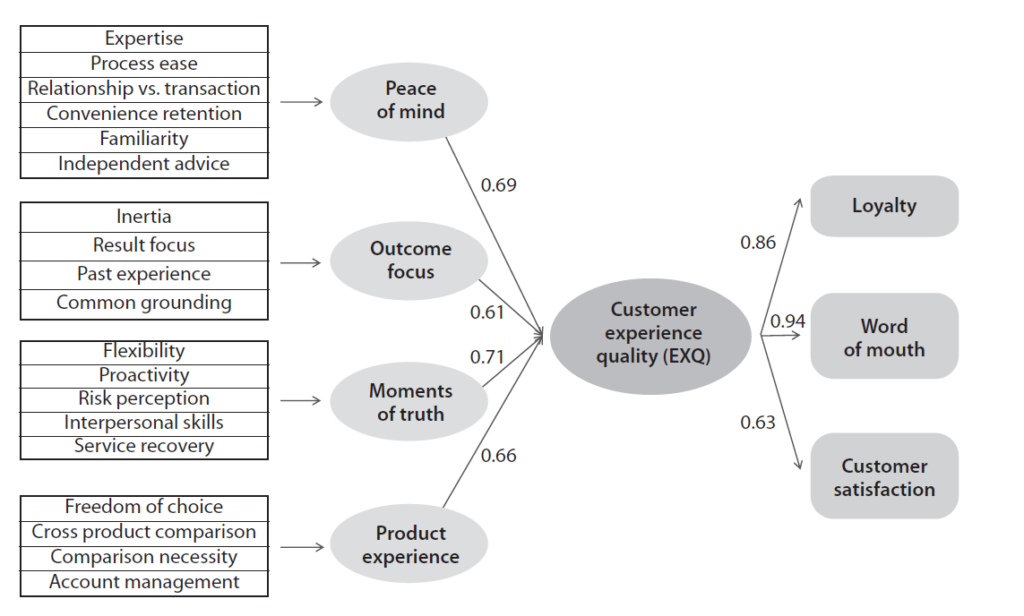

The measurement scale for measuring the quality of the customer experience

Maklant et Klaus (2011) propose a scale to measure the quality of the customer experience. This scale is based on 4 factors which they call “peace of mind”, “outcome focus”, “moments of truth”, “product experience” (see graph below).

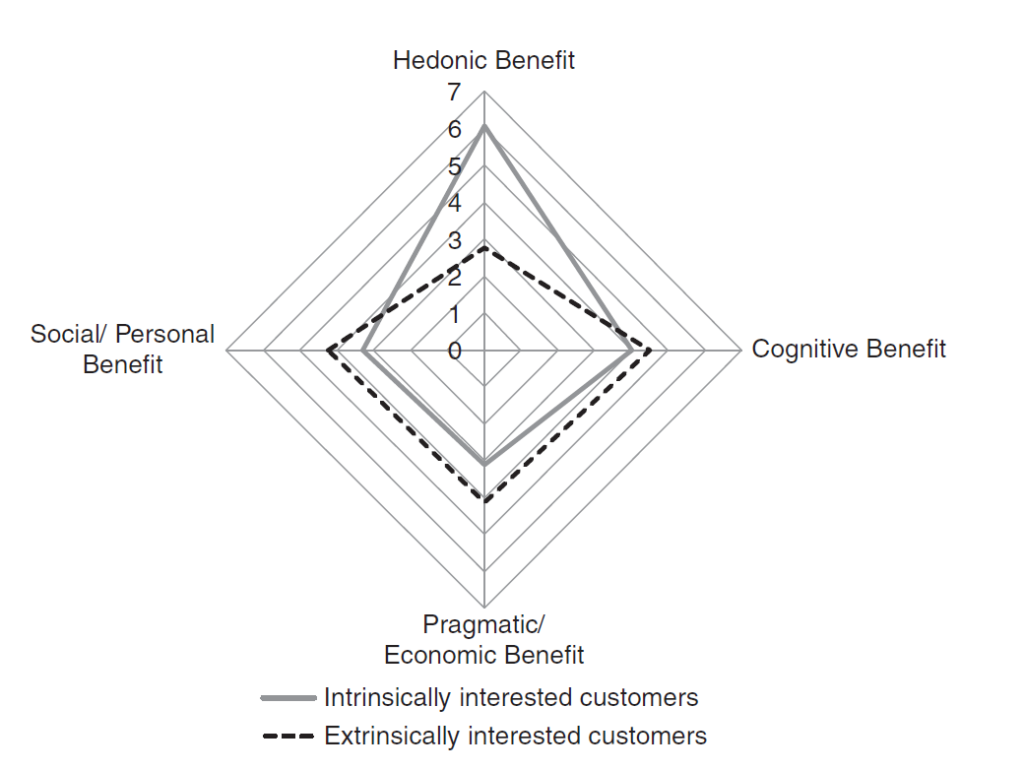

The scale for measuring customer experience in co-creation processes

The term “co-creation” has now become part of the common language. It refers to a collaboration between the customer and the company to develop or improve a product or service. The benefits that customers derive from these co-creation processes form a “customer experience” that Verleye (2015) articulates around 4 factors: hedonic, social/personal, cognitive, pragmatic/economic.

The Global Customer Experience Measurement Scale

Markus Gahler and his colleagues Michael Paul and Jan Klein have been developing for some years now a scale based on 6 dimensions: affective, cognitive, relational, physical, sensory and symbolic. This scale innovates by adding the “symbolic” dimension as a contributor to the customer experience. To find out more about this scale’s development, we refer you to the articles we published in 2018 and 2019. According to the latest news, this customer experience measurement tool should officially be launched in 2021.

Sources

Fournier, S. (1998). Consumers and their brands: Developing relationship theory in consumer research. Journal of consumer research, 24(4), 343-373.

Holbrook, M. B., & Hirschman, E. C. (1982). The experiential aspects of consumption: Consumer fantasies, feelings, and fun. Journal of consumer research, 9(2), 132-140.

Hultén, Bertil. “Sensory marketing: the multi-sensory brand-experience concept.” European Business Review 23.3 (2011): 256-273.

Kotler, P. (1973). Atmospherics as a marketing tool. Journal of retailing, 49(4), 48-64.

Lee, S., Jeong, M., & Oh, H. (2018). Enhancing customers’ positive responses: Applying sensory marketing to the hotel website. Journal of Global Scholars of Marketing Science, 28(1), 68-85.

Lemon, Katherine N., and Peter C. Verhoef. “Understanding customer experience throughout the customer journey.” Journal of marketing 80.6 (2016): 69-96.

Maklan, S., & Klaus, P. (2011). Customer experience: are we measuring the right things?. International Journal of Market Research, 53(6), 771-772.

Maklan, S. (2012). EXQ: a multiple‐item scale for assessing service experience. Journal of Service Management.

Vargo, Stephen L., and Robert F. Lusch. “Evolving to a new dominant logic for marketing.” Journal of marketing 68.1 (2004): 1-17.

Verhoef, P. C., Lemon, K. N., Parasuraman, A., Roggeveen, A., Tsiros, M., & Schlesinger, L. A. (2009). Customer experience creation: Determinants, dynamics and management strategies. Journal of retailing, 85(1), 31-41.

Posted in Marketing.