In this article, we present the results of a survey we conducted among employees practicing remote work. The results show that cheating is a widespread practice.

![Remote work: are employees cheating? [Survey]](https://5cc2b83c.delivery.rocketcdn.me/app/uploads/telework3.png)

Since the democratization of remote work in the wake of the health crisis, many companies are questioning its concrete effects on productivity, innovation, and especially how employees report their activity. For behind the image of the autonomous remote worker lies a more nuanced reality. Between ineffective control, reporting of unworked hours, and relaxed professional obligations, how can the rigor of remote workers’ practices be ensured?

Following our survey on Generation Z, we turned our attention to another aspect of the Human Resources world: remote work. We sought to understand to what extent the reporting of hours worked remotely reflects reality. What are the differences across generations? Which time-tracking tools are most effective? Our analysis highlights contradictions that invite us to rethink the very notion of control in the context of remote work. You can download our full study at the end of this article.

Contact us for your HR studies

Remote work and cheating: key figures

- More than 1/3 of companies implement no control mechanism for hours worked remotely. Generation Z is most often subject to control via software or a mobile application.

- 52% of employees work remotely 2 to 3 days per week. Those working remotely 4 days per week are the least rigorous in logging hours and less compliant with their work time obligations.

- Millennials and Generation Z admit to reporting more hours than they actually worked:

- 37% of millennials and 31% of Generation Z do so often

- 31% of millennials and 32% of Generation Z do so always.

- More than 30% of remote workers monitored via software or an Excel list always report more hours than they actually worked. More than half of those monitored via a mobile application do so often.

Control mechanisms and self-assessment

In general, when a control of hours worked remotely is implemented in companies, it is done via software or a mobile application where the employee must log their hours. However, note that in more than one-third of cases, no form of control is implemented. Employees thus have no records to provide to their employer. Regarding differences across generations, Generation Z is the most controlled, via software or a mobile application.

We can question the rigor with which a remote worker tends to ensure that the logging of work time is accurate. In other words, to what extent will the number of hours they report on control devices reflect the reality of the hours they worked during the day? It is interesting to note that millennials are the most likely to consider themselves highly rigorous in this regard.

More than half of our respondents (52%) work remotely 2 to 3 days per week (figure on the y-axis of the graph above). They belong to a category we could call “moderate remote workers.” However, we observe that, in general, the number of remote work days has no impact on employees’ self-assessment of their own rigor in logging hours. The only exception is employees who work remotely very often (4 days per week). These, unlike others and even compared to full-time remote workers (5 days per week), report being only “fairly rigorous.” The same applies to work time obligations. Once again, it is these highly regular remote workers who are less inclined to comply, even though full-time remote workers comply as much as others.

The question can also be approached from the opposite angle, asking remote workers how often they report hours exceeding those actually worked. The results are striking: 37% of millennials and 31% of Generation Z acknowledge that this practice is frequent. At the same time, nearly one-third of millennials (31.62%) and Generation Z (32.93%) admit that their reports are always falsified. These admissions directly contradict the rigor previously reported by these same groups.

The reasons leading remote workers to deliberately provide false reports of their remote work hours are varied. Personal obligations and family matters top the list, followed by recovering unpaid hours. We observe no significant generational differences. However, we note a slightly higher percentage among women for these two main reasons.

None of the control methods considered is stringent enough to prevent remote workers from reporting more hours than they actually worked.

Excel, app, software… not enough to curb inflated reports!

Nearly one-third (30.77% to 31.79%) of employees who must log hours worked in an Excel list or via software admit they always report more hours than they actually worked. More than half of employees who log hours via an application often report a higher number of hours. It appears that none of the control methods considered is stringent enough to prevent remote workers from reporting more hours than they actually worked.

Yet, as we have just seen, respondents mostly claim to be rigorous or very rigorous in accurately logging work time. At the same time, they admit to reporting additional hours frequently. This discrepancy raises a key question: are work hours truly recorded with sufficient rigor, or does the tendency to manipulate these reports remain dominant? A paradox that shows the reliability of logged hours deserves further exploration.

Contact the IntoTheMinds firm for your studies

What about Generation Z?

Generation Z stands out for more frequently managing personal matters during remote work. This practice is rather rare and occasional for Generation X.

These younger remote workers, born from 1997 onward, are also more likely to admit they do not respect their work time obligations when working remotely. Along with millennials, they also claim to take more breaks during remote work than when in the office.

However, where Generation Z surpasses their immediate elders is in the time spent browsing social media during remote work hours, which exceeds the time they allocate to this activity when at the office.

Where Generation Z surpasses their immediate elders is in the time spent browsing social media during remote work hours

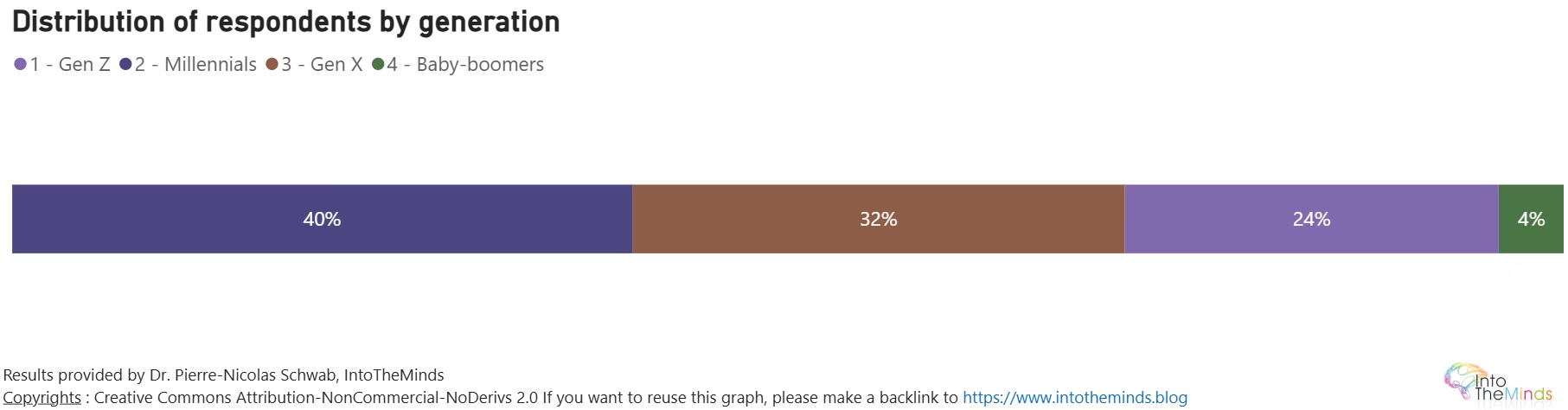

Respondent profile: relevance of baby boomers

Although our analyses include a generational distribution of respondents for the entire questionnaire, we chose to exclude baby boomers (61 to 79 years old) from our interpretations due to their very low presence in our sample (4.23%). A group like this, increasingly approaching retirement age, is no longer as relevant for comparison with subsequent generations regarding their remote work behavior.

Millennials, on the other hand, are the most represented in our sample (39.95%), followed by Generation X (31.73%). Generation Z alone accounts for nearly a quarter of our sample (24.09%).

Intensive work, vague reporting: a new norm?

Remote workers’ assessment of their productivity compared to office work is markedly positive. Across all generations, the vast majority of respondents note that their productivity is higher when working remotely than it would be in person.

Similarly, remote workers (particularly millennials) report working more intensely during remote work than at the office. Does this sense of productivity reduce the tendency to report unworked hours? Or, conversely, are false reports the result of the most efficient remote workers, capable of accomplishing more in less time and thus more tempted to hide periods of inactivity? Our results lean toward the second option, as it is indeed the profiles identifying as the most productive who also admit to reporting additional remote work hours.

As remote work becomes a permanent feature of our organizational models, it becomes essential to question the reliability of remote work time-tracking tools and, more broadly, the forms that control can take in a remote work context. It is less about increasing surveillance and more about reinventing the conditions for mutual engagement based on trust and shared responsibility.

![Illustration of our post "LinkedIn Top Voice: who are these influencers? [Research]"](https://5cc2b83c.delivery.rocketcdn.me/app/uploads/algorithme-linkedin-2022-120x90.jpg)

![Illustration of our post "Digitization: food & beverage industry companies lag far behind [Research]"](https://5cc2b83c.delivery.rocketcdn.me/app/uploads/marche-alimentation-bio-long-120x90.jpg)