In this 9th episode of the mini-com course series, Emmanuel Tourpe treats us to an analysis of the function of laughter in communication.

This analysis calls, of course on the work of Bergson that Emmanuel has the gift to make available to everyone.

Mini-com course N°9

Shared humour… the exchange of laughter

Why is laughter communicative – like boredom, for that matter? Everybody has seen the Name of the Rose – and knows the secret behind the great library that was burnt down and the motive for the crimes in the monastery: they wanted to hide a “treatise on laughter” by Aristotle, to keep pious souls from any entertainment.

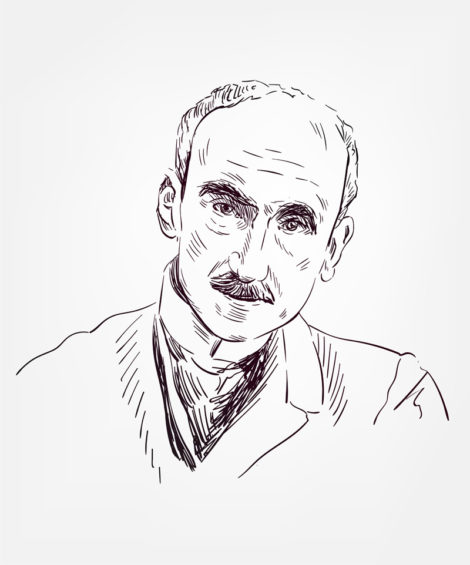

If it is true that the old Greek thinker made laughter the characteristic of man (man is the only animal that laughs”) it is not him, but a great French philosopher who wrote it much later. Henri Bergson – objectively not a comedian – did indeed look into the causes of laughter in 1900 – in work with a long mature title that must have taken him a long time to find: “Le Rire”! Well in real life there was a subtitle a little more sought-after: “Essay on the meaning of the comedian”. This doesn’t make you want to invite Mr Bergson to host a family party. But fine. By the way: pronounce [Bergsonne], which rhymes with bonne, not [Bergson], which rhymes with a ton.

There are a lot of ideas in this book that, quite frankly, will not cheer anyone up. It’s even pretty chilling: “Laughter is an anaesthetic for the heart”. Gulp. “It’s social bullying.” Re-gulp. You can tell the Bergson’s didn’t have any foo-foo jokes at dinner. But aside from that very negative judgment, Bergson has a fascinating idea: to make us laugh at something that introduces something mechanical into our lives. Well, that’s not very nice for all the Brice de Nice and other comedians either: the idea is that laughter is provoked a kind of killing of the living, an automatic side that thwarts.

Example: so and so is walking down the street, and slips on a banana peel. It makes the onlookers laugh because our man loses his manhood. He no longer controls the situation; he no longer moves as he pleases, something that escapes him happens, against which he can do nothing: he slips automatically, falls heavily. Nothing of his intelligence, of his freedom, of his life as a man, has any longer any place. A puppet has replaced the walker.

This is a very dark vision of humour that Bergson gives us – but let’s not forget that he writes at the same time as Baudelaire writes that all laughter comes from Satan. Gosh. It’s easy to see why it’s called the Belle Époque and not the Age of Laughter.

Much funnier was Thomas More, (+1535) whose witty words and famous puns did not make the king laugh, as he cut off his tongue as well as his head. Here is his famous prayer: “Give me good digestion, Lord, and also something to digest. Lord, give me humour so that I may derive some happiness from this life and share it with others”. There is indeed a mostly positive dimension to laughter. And even one of the foundations of communication. This is why laughter is communicative.

One laughs heartily because, contrary to what Bergson says, humour is not only aimed at the intellect, and is not by nature, evil. Socrates had even made it an instrument of self-awareness through his famous irony. For Kierkegaard, who was inspired by it, there is not even a possible existence without irony and humour: “He who does not dare, at any moment, to subject his seriousness to the test of mockery, is the true fool, the true comedian”. The poet Jean Grosjean has even written a stunning collection entitled “Christic irony”, proof if any were needed that one can laugh in high circles. If Jesus himself can laugh (the Gospel is full of jokes like this one: ‘it will be more difficult for a rich man to enter the Kingdom of Heaven than for a camel to go through the eye of a needle’ – authentic!)

What is it then that makes us laugh and is so communicative in laughter? The answer is probably the opposite of the one given by Bergson. It was given by a forgotten author called Auguste Penjon in 1893: “This brusque intervention which upsets order and introduces a pure game where seriousness thought it was sure to last, here is, if I am not mistaken, where to find the deep source of laughter”. We laugh because something happens, something that disrupts the course of things. An abnormality that suddenly attracts our attention and takes us out of the routine. The first spring of laughter is a surprise, akin to amazement. The insignificant being faded away, something new and sudden everything comes up. There is joy in seeing beauty. There is laughter to see the surprise. Both are uprooting from the flow of things, and come to provoke joy.

Like beauty, which is radiant, this surprise is communicative. We commune in this suspension of the everyday. We exchange our happiness. We are no longer isolated individuals, but suddenly our nature of reciprocity, of being together, arises. The unexpected shared: this is the essence of laughter.

For better or worse! The wittier the surprise, the higher will be the communion of humour; the more vulgar the surprise, the viler the exchange. There is this excellent dialogue in the film Ridiculous where the King asks an aristocrat to test his humour: “Make a witty remark about my Person” – “Sire, the King is not a Subject”. The delicacy of humour increases in proportion that the surprise is woven of wit, that the wit reveals itself as an event, a novelty. The community of laughter is more profound as the reason for laughing is more spiritual. Between the jokes of hogs and Desproges-like protrusions, there is a universe, measured by the spirit of the humour community that the elevation of spirit distinguishes.

This is what humour reveals about communication: it is based on communion and exchange; it grows and deepens as we are brought together by astonishment, wonder, surprise that there is being and not nothing, spirit and not mere matter. The most profound nature of communication is metaphysical – it places us, with laughter but also with beauty, before the most outstanding questions of existence.

Laughter is communicative because it is communion. – for better and for worse. “In the beginning is communion” (Maurice Nédoncelle) – who knows if there is not in God immense, eternal laughter, a story of infinite humour made of surprises between eternal Persons (Hans Urs von Baltasar)?

Posted in Misc..