What personal data are Internet users willing to share in exchange for better personalisation of the marketing offer? How to adapt your marketing strategy to get more data? This question is the subject of much debate at a time of the GDPR and the dawn of the entry into force of e-privacy. What data can a company still collect without fear that its customers will lose confidence? It is this tricky but crucial question that we propose to analyse today. A fascinating study has just been published that gives precise answers about the sharing of 17 categories of data based on ten marketing promises. This study will help you develop a truly effective data collection strategy.

Summary

- The cost of online personalisation

- The 17 categories of personal data

- The price of personal data

- What data are Internet users willing to share and in what context

- Conclusion

- Sources

Personalisation has a cost: that of personal data

In the digital age, the personalisation of content is a matter of course in all sectors of activity. From content delivery (Netflix, YouTube) to online advertising and e-commerce (Amazon, Alibaba), recommendation algorithms can increase business performance. Netflix estimates that its algorithms recommended 80% of the content consumed on its platform.

A recommendation algorithm proposed 80% of the content consumed on Netflix

The benefits of algorithmic personalisation are clear: more customer satisfaction and increased loyalty. But this increase in customer satisfaction and loyalty has a cost for the user: that of his data.

To fully understand the value of data, we must first talk about the different types of personal data.

The different types of personal data

Wadle et al. (2019) provide a very useful classification that also forms the basis for the study, which will be discussed later in this article. A total of 17 categories of personal data are identified (see below).

- racial or ethnic origin: ethnicity, nationality, skin color

- political opinions: opinions regarding current topics, voting behavior, political interest

- religious or philosophical beliefs: faith communities, conscience, values and moral concepts

- membership in associations: trade unions, associations, political parties

- genetic data: disease dispositions, DNA analyses, biological ancestry

- biometric data for unique identification: facial images, iris scan, fingerprints

- physical or mental health: health, medications, diagnoses, heart beat

- data concerning sex life: frequency, prevention, sexual orientation

- identification numbers: ID number, personnel number, social security number

- demographic data: date of birth, marital status, age, gender

- contact information: phone numbers, email addresses, home address

- physical characteristics: hair color, shoe size, weight, size

- financial situation: income, liabilities, capital assets

- professional training and occupation: obtained degrees, past occupations, attended schools and universities

- relationship with other persons: colleagues, frequency of contact, relatives

- physical and mental abilities: maximum grip force, IQ, visual acuity

- thematic interests: leisure activities, musical style, hobbies

The price of data

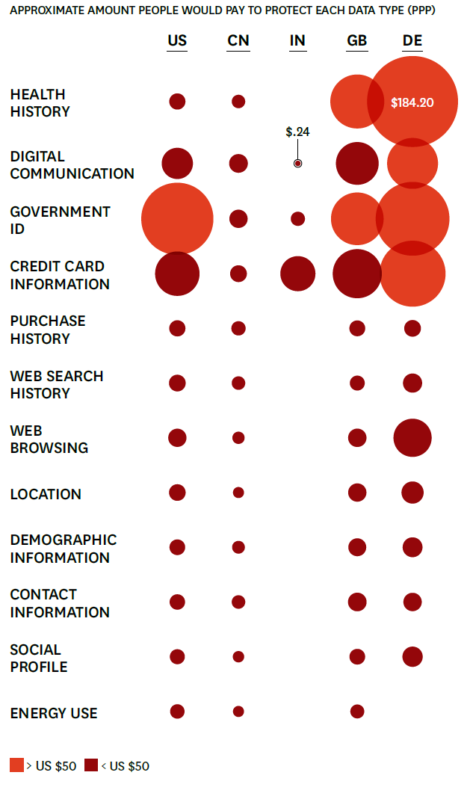

The price of data can be approached in two different ways: from the perspective of the company and the perspective of the consumer’s perception. Data are indeed “sold” between companies that collect them (they are actually “lent” for specific and limited use). Still, the economic value does not necessarily correspond to the “emotional” value that the consumer attaches to his data. In 2017, the German High Council for Consumer Protection published a very detailed report on the importance of customer data in business-to-business exchanges. The conclusions speak for themselves. A complete set of data on a user can reach 55 US$. For this price, you get data that we Europeans may consider extremely sensitive, such as credit history (see table below)

| Price per dataset | Description |

| approximately 1€ | for a “bulk” data set for one person and about 30 variables |

| up to 0,5€ | for a full address (Name, street, postcode) |

| 0,7 US$ | for travel and location data of a cyclist |

| up to 2€ | for a date of birth |

| 10 US$ | for mobile phone data (for one year and one user) |

| up to US$55 | for a complete set of data on a person, including date of birth, address, credit history |

The value of consumer data in exchanges between companies (source: Sachverständigenrat für Verbraucherfragen)

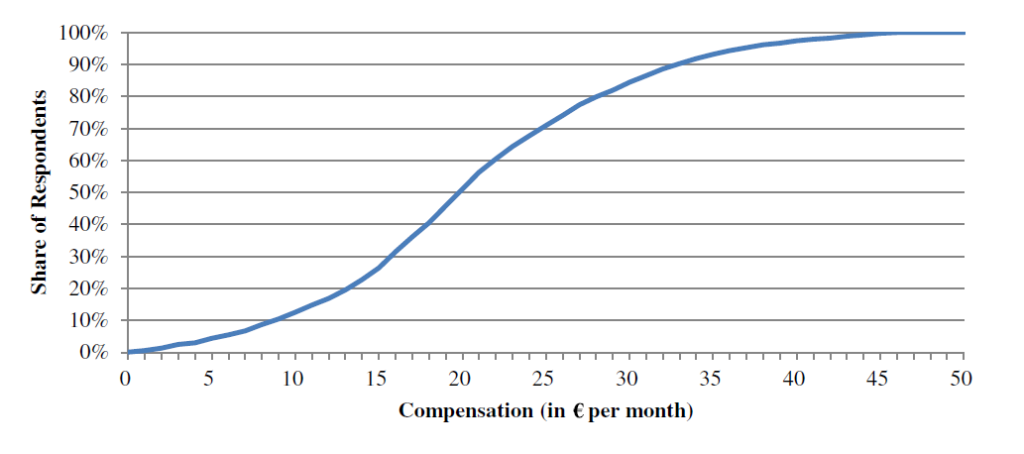

Roeble et al. (2015) also surveyed consumers about the value of their data. The subsequent evaluation made monthly, and the authors, therefore, obtained a monthly remuneration expected by consumers for sharing their data.

As you can see, there is little correspondence between economic reality (values often below €1) and consumers’ perception of the value of their data. This discrepancy can only lead to frustration since users overestimate the importance of their data in the light of an equation that is mainly unfavourable to them since they currently receive nothing.

50% of consumers would like to be paid more than €20 per month for sharing their personal data

The sharing of personal data depends on the context

The willingness of Internet users to share their data depends strongly on the context of data collection, as Roeble et al (2015) showed in a quantitative study.

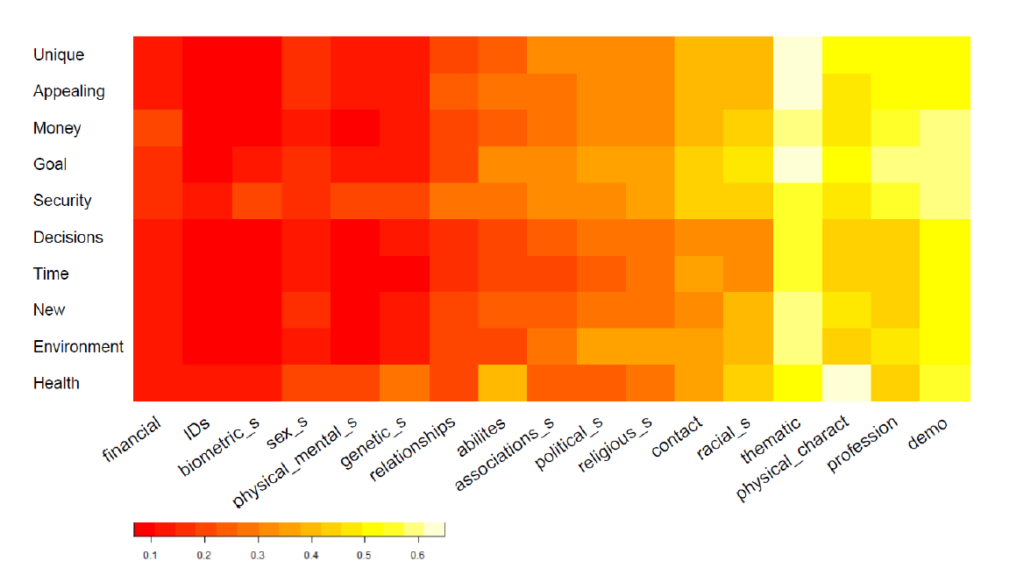

The fascinating study by Wadle et al. (2019) confirms this and demonstrates that it is the importance of the benefit perceived by the consumer that is decisive in the sharing of his or her data.

The study was conducted in Germany with 1121 people who answered an online questionnaire. They had to evaluate their propensity to share their data (classified into 17 categories, represented on the abscissa axis) according to different promises: better personalisation, more security, more time saving, better environment, smoother decision-making, improved health. The various benefits indicated in order in the diagram below.

The results show that users easily share some types of data ( for example, demographic data) in any context; others, on the contrary, are perceived as highly confidential and very little shared with third parties. This is the case for financial, biometric, sexual and genetic data.

How to read the graph ?

The 17 categories of personal data, as indicated in abscissa (financial, IDs). Marketing promises are in order (unique, appealing). The redder the box at the intersection of a data category and a marketing promise, the less likely it is that the user will share this type of data to obtain the marketing promise.

Some concrete examples:

- German users are seldom ready to share their financial data; the only (slight) exception is for monetary gain

- 60% of German users are willing to share their demographic data regardless of the promise made

- nearly 70% of users would share their hobbies and interests (thematic) to benefit from better personalisation.

Conclusions

The results of the study presented above allow marketing professionals to identify how to proceed to obtain more data from users. Maintaining customer trust is essential. Precise tactics, even surgical ones, must, therefore, be used to collect useful data within a correctly locked legal framework.

Sources

- Miltgen, C. L., & Peyrat-Guillard, D. (2014). Cultural and generational influences on privacy concerns: a qualitative study in seven European countries. European Journal of Information Systems, 23(2), 103-125.

- Morey, T., Forbath, T., & Schoop, A. (2015). Customer Data: Designing forTransparency and Trust. Horvord Business Review, May, 1.

- Palmetshofer, W., Semsrott, A., & Alberts, A. (2016). Der Wert persönlicher Daten: Ist Datenhandel der bessere Datenschutz. Veröffentlichungen des Sachverständigenrats für Verbraucherfragen. Berlin: Sachverständigenrat für Verbraucherfragen (SVRV).

- Roeber, B., Rehse, O., Knorrek, R., & Thomsen, B. (2015). Personal data: how context shapes consumers’ data sharing with organizations from various sectors. Electronic Markets, 25(2), 95-108.

- Wadle, L. M., Martin, N., & Ziegler, D. (2019, June). Privacy and Personalization: The Trade-off between Data Disclosure and Personalization Benefit. In Adjunct Publication of the 27th Conference on User Modeling, Adaptation and Personalization (pp. 319-324). ACM.

Illustrative images: shutterstock

Posted in big data.