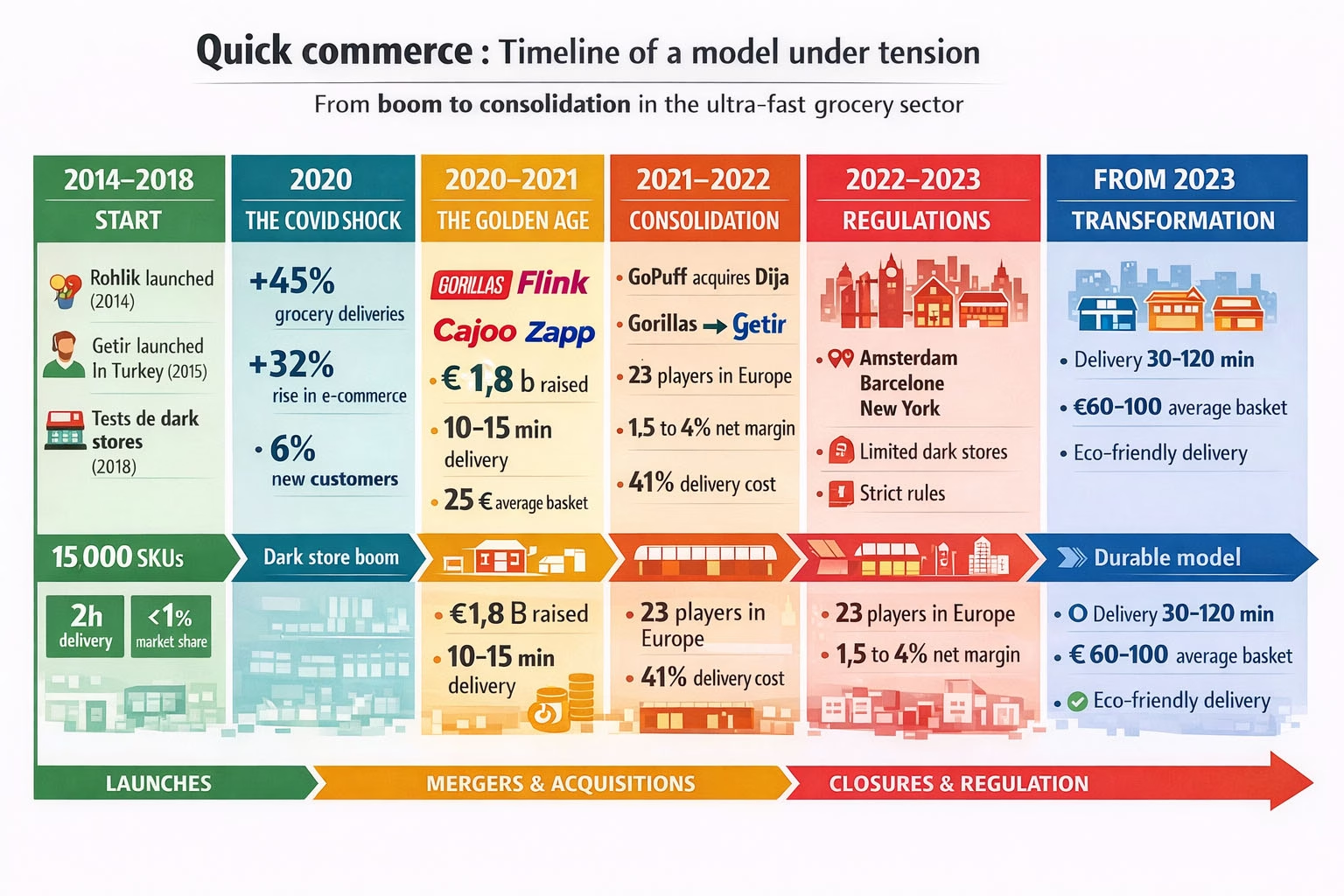

In this article, we analyze the phenomenon of quick commerce, from its origins to its decline. We explain its weaknesses but also its future with drone delivery.

Quick commerce has radically transformed our consumption habits. The promise was enticing: receive your purchases in less than 15 minutes. But behind this promise lay a complex ecosystem that disrupted traditional retail codes and faced legal challenges. Today, the quick commerce of 2020-2022 is moribund but reappearing in new forms. Our marketing consulting firm has analyzed the situation to trace the evolution of quick commerce and provide you with an analysis of its future.

Contact IntoTheMinds for your marketing studies

Quick commerce in statistics

- €1.8 billion invested in quick commerce startups in 2021

- 10 min: delivery time promised by Gorillas, Flink and Getir

- 2 hours: delivery time voluntarily adopted by Rohlik to improve route profitability (2021)

- 23: number of quick commerce players identified in the European market in 2021

- 50: number of dark stores opened in four months in 2021 by Flink in Europe

- €25: average basket size for quick commerce players in 2021

- €60-100: average basket size claimed by Rohlik in 2021

- €300 million: revenue achieved by Rohlik in 2020

- €110 million: business volume announced by Gorillas less than a year after its creation (2020)

- 1.5-4%: estimated net margin for online grocery, including quick commerce models like Getir, Flink or Cajoo (2021)

- 6%: share of consumers who used a home delivery service for the first time, including Getir, Uber Eats and Deliveroo in 2020

- $7.5 billion: valuation reached by Getir after its Series D (2021)

- €1 billion: valuation threshold crossed by Gorillas in less than a year, becoming Europe’s quick commerce unicorn (2021)

The origins of quick commerce: a revolution in stages

To understand the emergence of quick commerce, we need to go back to the mid-2010s. This period marks the beginning of a “wave-by-wave” digitalization of grocery retail that gradually transformed consumer habits.

The first wave, food delivery, laid the foundations. Platforms like Uber Eats established new reflexes: mobile ordering, real-time tracking, algorithmic optimization of last-mile delivery. The numbers speak for themselves: in 2020, Uber Eats reported $4.8 billion in revenue (+152% year-on-year), 66 million active users and a presence in 6,000 cities with 600,000 partner restaurants.

This “education” of consumers to near-instant delivery paved the way for a logical extension: why limit yourself to meals when you can deliver groceries? McKinsey then estimated the global food delivery market at over $150 billion, a volume that had tripled since 2017.

Then came the health crisis, a real accelerator of this transformation. In France, online sales jumped +32% in 2020 and e-commerce grew by +8.5%. Even more revealing: grocery home deliveries exploded by +45% in 2020.

This sudden demand brutally revealed the limits of existing models. During lockdowns, delivery times sometimes reached ten days, with stockouts and service degradation. The customer signal was clear: the Net Promoter Score of grocery delivery services dropped to -29 in France (compared to +9 in the US).

Paradoxically, this crisis also revealed the sector’s enormous potential. Studies show that a successful experience creates a virtuous circle: 82% of satisfied consumers share their experience, 73% are more likely to try new offers, and 74% increase their spending by about 12%.

Dark stores: the innovation that changes everything

This is where dark stores became the structuring element of modern quick commerce. These urban mini-warehouses, often 200-300 m² (sometimes less), closed to the public, revolutionized local logistics. This is what’s called the “last mile” and it’s generally the most complicated part of the supply chain to master.

The principle is very effective on paper. The assortment is deliberately limited (1500 to 2500 references) which optimizes picking operations and enables ultra-fast delivery promises. In the most efficient dark stores, order picking is organized to take 3 to 4 minutes per order, and some sites process over a hundred orders per day.

Geographic coverage is crucial. Each dark store serves a dense area, typically 150,000 to 200,000 inhabitants, accessible within ten minutes. This logic explains why Paris, London, Berlin, Amsterdam or Moscow became battlegrounds: urban density theoretically makes the volume economic equation possible.

This infrastructure allowed quick commerce players to offer delivery times that seemed impossible just a few years ago. But it also represents a considerable investment and a bet on the evolution of urban consumption habits. It also came with major legal issues that led to the death of dark stores and, by extension, quick commerce in many cities. We refer you to our study to learn more.

The funding race: when money flowed freely

The 2020-2021 period marked a sudden acceleration of the sector, fueled by massive capital inflows. The numbers were staggering. In 2021, €1.8 billion was invested in delivery startups, making quick commerce one of the most “watered” segments of foodtech.

Take the example of Gorillas, created in May 2020 in Germany. The company raised €36M in December 2020, then €244M in March 2021 from prestigious investors like Tencent. In September 2021, it broke records with a $950M raise, while announcing €110M in business volume in 2020.

Flink illustrates this frantic race: after raising $52M in March 2021, the startup closed $240M in early June 2021 with Prosus, Bond and Mubadala Capital. The company claimed to have opened 50 dark stores in 4 months across 18 European cities – an average of one dark store every two days!

This dynamic extended far beyond Europe. Getir, the Turkish pioneer in the sector (launched in 2015), raised over a billion dollars in 2021 and reached a valuation of over $7.5 billion. In the US, Gopuff already operated more than 500 sites in 500 American cities and was valued at $15 billion after raising $1 billion.

French players: between innovation and economic realism

France quickly became a testing ground for quick commerce. Several players deployed their strategies there with differentiated approaches.

Cajoo bet on a model with 1,500 references, service until midnight and an ambition to cover 20 cities by the end of 2021, after raising €6M in seed funding. The company aimed to cover 150,000 to 200,000 inhabitants per dark store.

Frichti stood out with a more integrated approach. With 450,000 customers in six years, the company launched Frichti Everyday, a private label of 120 products banning 72 additives. Even more remarkably, Frichti claimed profitability: its dark stores became profitable in 3 to 6 months and the breakage rate fell from 30% to less than 5%, helped by a high density of tech teams (one third developers at headquarters).

Traditional retailers weren’t inactive. The example of Auchan in Talence illustrates a pragmatic approach: a 150 m² dark store in the basement with 1,500 references and a promise of delivery in less than 15 minutes. The announced investment remained modest (less than €10,000, with store assets already in place), and after 2.5 weeks, about 50 orders were processed with an observed basket “rather close to €40” versus the initially expected €25.

Strengths and weaknesses: the economic equation under pressure

Quick commerce has undeniable advantages. It meets a real need for convenience and simplicity, transforms the customer experience by integrating app, payment, preparation and delivery. It also offers powerful marketing possibilities: targeted promotions, subscriptions, personalization and potential data monetization.

But the structural weaknesses are just as obvious. In grocery, margins remain structurally low: between 1.5% and 4% for online grocery, while the last mile represents 41% of supply chain costs.

The 10-15 minute model complicates route optimization: a delivery person often delivers just one order rather than three, and returns empty. The limited assortment reduces the ability to compensate with higher-margin categories. Speed requires dense coverage, meaning tied-up capital and high urban rents.

Faced with these challenges, players have explored several levers:

- increasing delivery fees (+€1 to +€2 according to analyses)

- reducing promotions

- improving purchase conditions

- increasing delivery personnel productivity

- scaling up volume

But despite this, quick commerce has failed to reach equilibrium.

Alternative models: speed isn’t everything

This economic tension explains the emergence of alternative models. The 10-15 minute promise remains spectacular but not necessarily the most viable.

Rohlik offers a different path that seems more sustainable:

- two-hour delivery

- very wide catalog (17,000 products)

- average basket of €60 to €100

With €300M in revenue in 2020, over 750,000 customers and claimed profitability in its home country, the Czech company became a unicorn (valuation over €1 billion) and expanded to Austria, Hungary and Germany.

This comparison is instructive: by extending the delivery time, you increase sharing, basket size, predictability and thus potential profitability.

Amazon and Monoprix illustrate another “asset-light” approach: rather than creating dedicated warehouses, they rely on existing networks. Their same-day delivery offer is based on 6,300 references including 1,600 private labels, on a two-hour slot between 2pm and 10pm, with free delivery for orders over €60 (otherwise €3.90).

Consolidation and outlook: towards market maturity

The M&A movement is naturally accelerating. When fixed costs rise, the market tends to consolidate. Gopuff perfectly illustrates this in Europe through its acquisitions: Fancy in May 2021 and Dija in August 2021, with the announcement of investing “several hundred million dollars” in Europe.

This consolidation is accompanied by a rationalization of business models. The “real economic battle” could be fought in data exploitation and additional revenues, not just product margins.

In the background, logistics is becoming a global battlefield. Amazon opens permanent dark stores (like the Whole Foods one in Brooklyn in 2020), its online grocery sales tripled in Q2 2020 and its grocery delivery capacity increased by over 160%. Over ten years, its total global storage space grew from 1.6 million to 26.6 million m², with 1,058 warehouses worldwide.

What future for quick commerce?

Overall, the quick commerce timeline tells a coherent story:

- food delivery established the habit

- Covid revealed last-mile weaknesses

- dark stores became the industrial tool to produce speed

- capital influx financed dazzling expansion

- economic viability became dependent on volume, basket size and consolidation.

The numbers reveal this tension: although the market share is marginal (0.5% of grocery purchases), its momentum was strong and investments followed (€1.8 billion). But the entire value chain ran up against resident opposition to dark stores, legislative aspects, and ultimately everything stopped abruptly.

What can we learn from this adventure? Quick commerce proved its ability to transform urban consumption habits but encountered, because of dark stores, insoluble legal problems. To this was added an economic equation that was also very difficult to solve (the cost of the last mile). Quick commerce today is a pale copy of what it was a few years ago. The future will tell if this logistics revolution can find its balance between customer promise and economic reality. But one thing is certain: 15-minute delivery by humans won’t return. Perhaps drones will be the solution. They could eliminate high delivery costs and increase range, potentially allowing dark stores to be located further from urban centers and their numbers to be rationalized.

Frequently asked questions about quick commerce

Is quick commerce really profitable?

Profitability remains the sector’s major challenge. With structurally low margins (1.5% to 4%) and last-mile costs representing 41% of expenses, few players reach equilibrium. Frichti was an exception in claiming dark stores became profitable in 3 to 6 months. But ultimately, profitability means nothing if the business suffers from legal problems.

Why are dark stores so important?

Dark stores are the heart of the economic model. These 200-300 m² mini-warehouses enable ultra-fast picking (3-4 minutes per order) thanks to a reduced and optimized assortment. Without them, the 10-15 minute delivery promise that differentiates quick commerce from traditional e-commerce would be impossible to keep. However, dark stores have been banned in many cities, ending the quick commerce chapter.

Will quick commerce replace supermarkets?

No, quick commerce remains complementary in its new form (deliveries in a few hours). It still represents only 0.5% of grocery purchases and focuses on convenience shopping in dense urban areas. Supermarkets retain the advantage for major shopping trips, fresh products and less dense areas where the quick commerce economic equation doesn’t work. The dense network of convenience supermarkets creates strong competition, especially in a context of declining purchasing power.

Who are the main market players?

The landscape is evolving rapidly. Getir (Turkey) and Gopuff (US) dominate with billion-dollar valuations. In Europe, Gorillas and Flink raised massively but face profitability challenges. In France, Cajoo and Frichti are trying differentiated approaches, while traditional retailers like Auchan are experimenting with their own solutions.

Is quick commerce environmentally sustainable?

This is debatable. On one hand, individual delivery multiplies trips. On the other, sharing via dark stores and using electric bikes can reduce carbon footprint compared to individual car trips. The impact largely depends on urban density and the transport mode used for deliveries.

![Illustration of our post "Dark stores: statistical analysis and outlook [Study]"](/blog/app/uploads/dark-store-120x120.jpg)

![Illustration of our post "Recruitment by co-optation: state of the French market [survey]"](/blog/app/uploads/shutterstock_2070689711-scaled-e1688048891453-120x90.webp)