On 5 March 2020, the Secretary of State for Economic Transition in Brussels, Barbara Trachte, published on her LinkedIn account an interactive map of the street names of the Belgian capital. The data reveals that only 6.1% of the streets in the Belgian capital are named after women. It was learned at the same time that an ordinance was being prepared to facilitate the feminisation of street names through popular participation. The first case of use will be the Leopold tunnel in Brussels. Already in disgrace, the Belgian monarch had enough streets, avenues, squares and other squares across the border and could well abandon a tunnel.

In this article, I have gone deeper into the subject of statistics on female street names, plunged into the origin of street names. Finally, in a more light-hearted way, I approach the heart of the matter in a context conducive to parity between men and women.

The origin of the Brussels street names project

We learn in the press that the paternity (pardon the maternity :-)) of the project “Towards Equal Street Names” is to be found in a public initiative for more equality between men and women. And I am the first to say that it is necessary. For this purpose, 15000€ have been allocated to the non-profit association Open Knowledge Belgium to make this map. Technical details are available here.

Street names and masculinism: a global trend

The observations made in Brussels are nothing extraordinary. Streets named after women are in the minority in any country.

“The proportion of women is estimated at 0.6% in Marseilles, 1.2% in Clermont-Ferrand, 1.1% in Lyon, 1.6% in Brest… Thus, perfectly translating the sexism of French society,” says an article in the French weekly l’Express. In Paris, it is only 6% according to a study by Le Figaro.

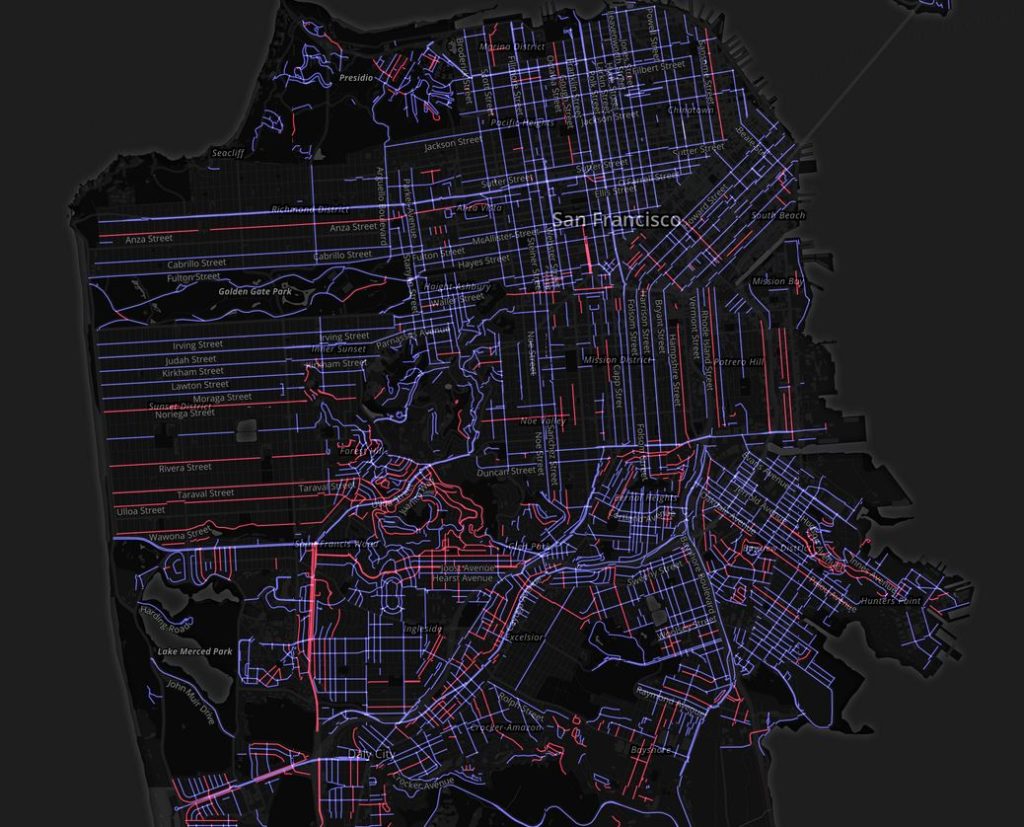

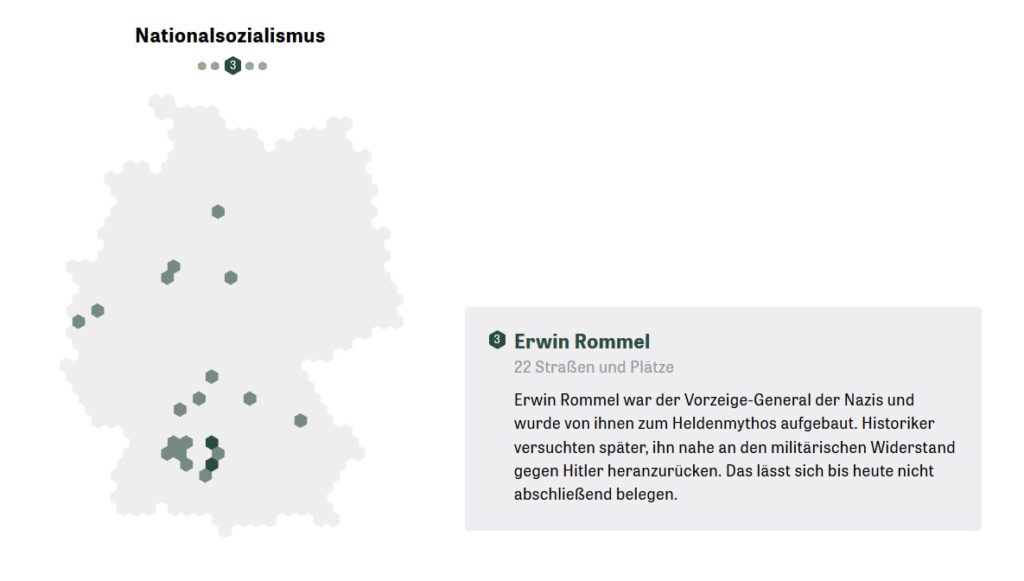

In Germany, women’s names are also in the minority, as revealed by a thorough (and visually beautiful) work by the daily Die Zeit. In London, the proportion seems much higher (27.5%) but is still lower than that of men. A Mapbox team carried out the same exercise as early as 2015 for San Francisco, Mumbai, New Delhi, Chennai (see map below) and the results are the same everywhere.

In Italy the situation is similar: according to the sources, the percentage of streets named in honour of a woman varies from 4% to just under 12%. In Milan, only 130 streets are named after women. It remains to be seen; however, what the origin of this phenomenon is.

Naming the streets: a practice that is rooted in the past

Street names are primarily a reflection of the past. Jean Bouvier, a historian, tells us about the city of Aix-en-Provence:

“Until about the 17th century, street names were exclusively defined by the inhabitants themselves, in a sort of vast collective creation. Far from being insignificant, they constitute the memory of a city and bear witness to its history: landscapes, economic activities, cultural and political life… A large number of Aix’s arterial roads owe their name to this category.”

The same toponymic process applies in the United States. As Algeo (1978) shows, street names are rooted in local history and activity when American cities are created. The second wave of name creation is distancing itself from local history and adopting more generic names with commemorative virtues. Azaryahu’s various research projects focus on tracing the history of cities based on the study of street names as sociological objects. There can be no doubt that street names are reflections of society, and in particular of the very masculine character of society at the time.

Renaming the streets: first and foremost a political statement

In the Brussels project, the data is “summoned” to serve as a blank check for initiatives (including an ordinance to rename the streets) whose fragility is reflected in this statement by Nawal Ben Hamou. The Secretary of State for Equal Opportunities and member of the Socialist Party, says:

Increasing the visibility of women in the street is, in our opinion, one of the possible levers to promote equality between women and men in the public domain.

Nawal Ben Hamou

This statement reveals the fragility of the approach and the vacuity of the arguments. Ms Ben Hamou, using “in our opinion”, emphasises that the feminisation of street names has no basis, other than her conviction that it will help the cause of women. In fact, as Azaryahu (1996) shows, the names given to the streets are above all a reflection of a political agenda, a reflection of power at a given time. The vernacular names of the beginning are therefore replaced or supplemented (in periods of geographical expansion) by names that celebrate, here a victory, there a famous person. As Azaryahu shows, street names make it possible to read the history of a city, and it is in this precise context that the Brussels initiative must be placed. Changing one or more street names is nothing more than a testimony to the feminist movement. It is a witness to the political awareness of the role of women. Politicians then deem it necessary to solidify their agenda, their priorities, in the unconscious collective by the name of a street.

Feminising street names: yes, but to what effect?

The problem is that there is no evidence that this celebration of the female cause through toponymy will have any effect on the phenomenon of the necessary emancipation of women. For street names are present in the collective unconscious in the literal sense of the word. The memory of their origin is lost over time. And when you reveal it, a little old-fashioned perfume inevitably diffuses. The articles that do this are at best entertaining, at worst anecdotal. Le Figaro has produced a computer graphic of this type, and it is symptomatic that it is FigData that has stuck to it. Classical journalists have no doubt found the task too undignified. Ironically, it is “the data” that serves as an excuse here again.

Rewriting the past to shape the future?

The gesture made by the female politicians of Brussels is, therefore only political in scope. How can we honestly hope that the feminisation of street names can help to achieve an equal society? This element is anecdotal, and unless the population embraces it, it can only attract ridicule. One only has to read the comments that the Brussels ad has generated on social networks to be convinced of this.

Do we want to erase, by this gesture, the reality of a past that has often put men forward? What’s the point? Who still remembers past war heroes to whom a street name was dedicated? And besides, who cares?

Perhaps the best proof is to go to Germany. Despite an oppressive past, the use of artifices such as changing street names has not been generally applied. Thus, Hindenburg is still present on 438 street and square signs, and more surprisingly Erwin Rommel on 22. The “desert fox” as he was nicknamed was, however, an admirer of the Führer until his last days. And I’m not talking about the omnipresent traces of the communist past in former East Germany. Apart from the most striking examples (Karl-Marx-Stadt renamed in Chemnitz), there are plenty of references to the communist period.

Since street names are sociological objects with no value other than historical significance, let us leave them where they are and get on with other tasks. In a world, as disturbed as the one we are currently living in, are there not, in fact, other priorities than that of wanting to rename street names?

The real battle: restoring women’s confidence

The real priority is to go beyond the clichés and get to the roots of the problem. This task will no doubt take a generation because it must start at the earliest possible age. Young girls must be allowed to gain confidence in themselves, in their potential, and be given all the tools to fulfil themselves in society. Boys must be educated, and behaviour must be rectified. In particular, paternalistic and demeaning behaviour, which some people tolerate for fear of being pushed to the margins of a society that must be permissive or it will be accused of racism, must be corrected.

The obstacles to women’s entrepreneurship must be removed through a collective and political effort. But politics must not undermine its credibility (already at half-mast) by focusing on anecdotal evidence. The real outcome of this fight for greater parity is at stake.

If you want to learn more about the restraints on female entrepreneurship, we encourage you to listen to the podcast we have devoted to this subject with Florence Blaimont (WoWo Community). We have also produced a video (The World of Business series with Pierre-Raffaele) that gives an additional perspective on the subject (see below).

Sources

Algeo, J. (1978). From classic to classy: Changing fashions in street names. Names, 26(1), 80-95.

Azaryahu, M. (1996). The power of commemorative street names. Environment and planning D: Society and Space, 14(3), 311-330.

Illustration image: Shutterstock

Posted in Misc..