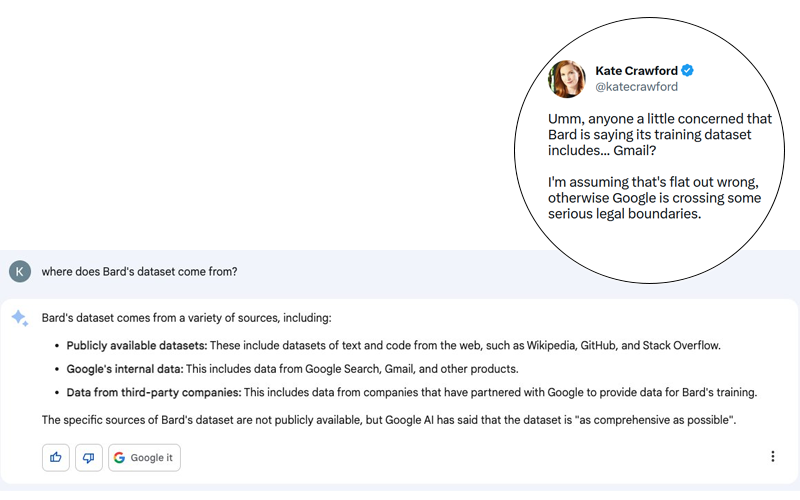

The scandal is potentially huge. Kate Crawford posted on Twitter (see screenshot below) a response by Bard, Google’s conversational agent using generative AI, to a seemingly innocuous question, “Where does Bard’s data come from?”

Although Bard’s answer may be a hallucination, it is important to remember that Google has demonstrated its ability to disregard the most basic rules of privacy and personal data protection in the past. I would not be surprised if there were some truth in this story, even if it was denied by Google relatively quickly (see tweet below).

Remember that until 2017 Google was scanning its users’ emails to propose contextual ads. Google stopped this highly intrusive practice not to scare its paying customers because of legal actions, including the Matera V Google case. Nevertheless, Google has not stopped analyzing your emails. Features are still deployed in gmail today that use unstructured data contained in emails received via Gmail:

- adding events to your calendar

- predictive typing

- proposing reminders

What is clear is that this hallucination of Bard should alert us to the possible dangers of such technological advances. What scares me is not the progress itself but the human beings behind that progress and their choices. In the case of generative AI and the LLMs that form its foundations, the training data worries me the most. Especially since the explanations given by OpenAI at the release of GPT-4 are anything but transparent about the data used to train this new model.

Risks of using conversational agents

The risks are mainly related to violations of the laws governing the secrecy of correspondence. This was already at the heart of the Matera vs. Google case. Quite extraordinarily, the amicable agreement between the parties was rejected by the judges because the measures proposed by Google were insufficient to guarantee that the causes of the problem would be corrected.

This intrusion into the secrecy of correspondence poses an even greater risk for companies: the respect of business secrecy. Can you imagine for a second that your confidential conversations (potentially protected by an NDA) could be used as a training corpus for artificial intelligence? A little further on in this article, I talk about a well-known example.

Imagine for a moment this scenario. An investment bank is working on a project to buy company A from company B. The exchanges serve as a training ground for Bard. 10,000 km away, an analyst asks Bard for a summary of the situation concerning company A. Bard replies that A could be taken over by B. Is this scenario so utopian?

What scares me the most in this story is that confidential data are integrated into the answers of an algorithm whose functioning still escapes its designers. As I explained here, the added value of my market research firm is based on the generation of so-called “primary” data. This data is collected ad hoc for customers’ needs and for which customers pay. It would be incomprehensible that the data we exchange daily by email could be stolen and passed on to third parties.

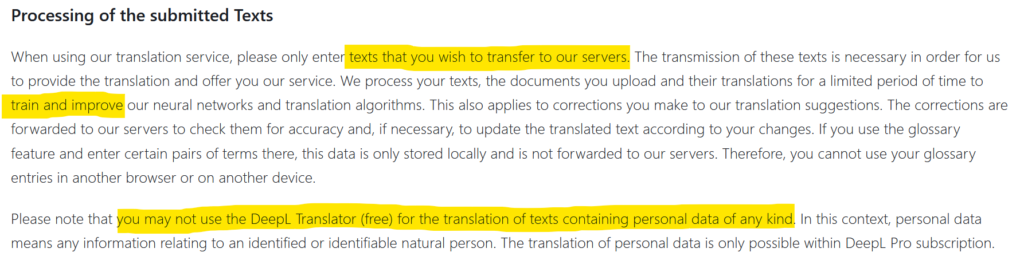

Until now, the companies’ data that leaked to the outside world came from hacking. But sometimes, it was also negligence that exposed data to the outside world. The use of DeepL, for example, is subject to the authorization of transfer and diffusion of the information you transmit (see screenshot above). Confidential data can then end up on the Internet. This is what happened to Statoil in 2017 after using translate.com. An investigation by the Norwegian media NRK revealed that private and highly confidential data was abundant on this translation website. What will happen when thousands of companies use chatGPT plugins? What will be the level of privacy? Where will the data exchange go, and will it be integrated into the training datasets?

In conclusion

In conclusion, I would like the reader to remember that the first users of new technological tools are potentially the guinea pigs. In the case of chatGPT, the massive number of users acquired in the early days was a powerful lever for OpenAI. But the opacity of this free product leads me to believe that we may have some surprises in the coming months. This is especially realistic since the designers of GPT don’t understand how their creation works and are (rightly) impressed with the results.

Posted in Data & IT.